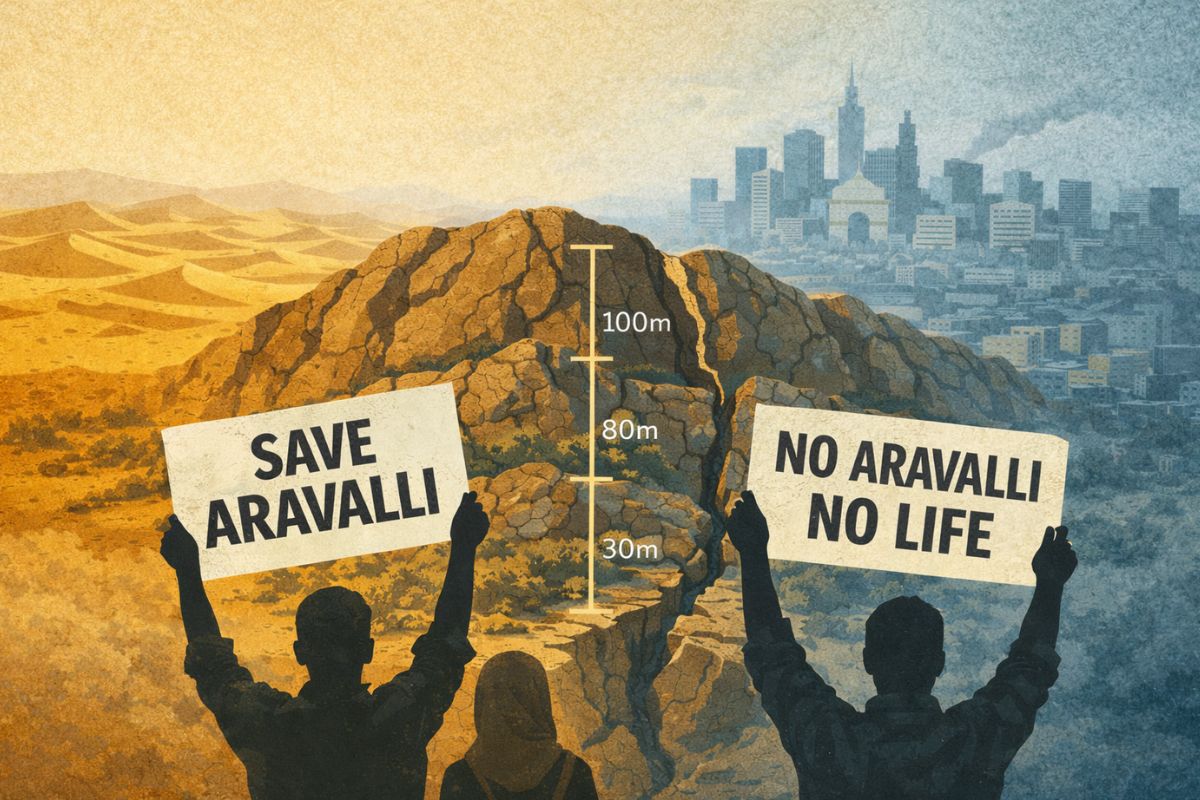

Protesters are filling the streets of northern India after the Supreme Court changed how the government defines the Aravalli hills. The court accepted a new rule on November 20, 2025 that says only hills rising at least 100 meters above the ground around them count as part of the Aravalli range.

Activists, politicians, and local people say this new height rule could remove protection from 90 percent of these vital hills. They worry that mining companies and builders will destroy areas that currently stop desert sand from reaching Delhi, store rainwater underground for millions of people, and block the Thar Desert from spreading east.

What Are Aravalli Hills?

The Aravalli range runs nearly 690 kilometers from Gujarat through Rajasthan and Haryana to Delhi. Scientists say these hills form the oldest mountain system in India. Time and weather have worn them down over millions of years, so they are not very tall anymore. But they still do important work for western and northwestern India.

The hills act like a wall that stops the Thar Desert from moving toward the crowded Indo-Gangetic plains. Their rocks soak up rainwater slowly and send it deep underground. This refills the water sources that supply Delhi, Gurugram, Faridabad, and Alwar. Major rivers like the Chambal and Sabarmati start in these hills. Farmers across several states depend on this water for their crops and living.

The hills also shelter forests, scrublands, and grasslands even though the area stays dry most of the year. Leopards, hyenas, nilgai, and many types of birds live here. For Delhi and nearby cities, the hills do one more critical job. They block dust storms and trap air pollution coming from the west.

Controversy Explained

The Supreme Court approved a definition that a government committee suggested. The rule says hills must rise at least 100 meters above the land right next to them to qualify as Aravalli hills. If two such hills sit within 500 meters of each other, the land between them also gets counted as part of the range.

The government says this height-based rule brings clarity. For many years, different states used different ways to decide which areas were part of the Aravallis. Some states used height measurements. Others looked at forest notifications. Some relied on old British-era laws. Mining companies took advantage of this confusion. They argued that certain hillocks did not legally count as Aravallis even though these areas connected to the hill system.

Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav defended the new rule on December 21. He said only 0.19 percent of the Aravalli’s total area of 1.44 lakh square kilometers would allow mining. He stressed that all land within 500 meters of qualifying hills stays protected no matter how high or low it is. “Stop spreading confusion! Only 0.19% of the total 1.44 lakh sq km area of Aravalli can be eligible for mining. The rest of the Aravalli is protected and secure,” Yadav wrote on social media.

The Union Environment Ministry released a statement saying officials will not grant new mining permits until they finish detailed studies following the November 20 order. The ministry said there is “no imminent threat to the Aravallis’ ecology” and the hills “remain under robust protection.” Officials argued the uniform definition would end disputes and stop random decisions about which land needs protection.

Why Environmentalists Are Alarmed

Environmental experts reject using height alone to decide protection. They say the 100-meter limit ignores how the Aravalli system actually works. Many critical parts like areas that refill groundwater, paths that animals use to move around, and low ridges fall below this height. But these areas still do vital work for the environment.

Professor Lakshmi Khan Sharma from the Central University of Rajasthan pointed out that most Aravalli hills in Rajasthan only rise 30 to 80 meters. The new definition would remove automatic protection from nearly 90 percent of the range. The Forest Survey of India used a different method that looks at slopes. This scientific mapping found 40,483 square kilometers of Aravalli terrain across 15 Rajasthan districts. The 100-meter rule would exclude 99.12 percent of the 118,575 Aravalli hills that scientists identified.

Water expert Rajendra Singh won the Ramon Magsaysay Award for his conservation work. People call him the “Waterman of India.” Singh warned the decision could destroy the range. “If this decision, meant to benefit one individual, is implemented, only 7 to 8 percent of the Aravalli will survive,” Singh told news agency PTI. He called for court challenges and public action to protect the hills.

Environmentalist Vimlendu Jha explained the wider problems to Times of India. “The mountain is not just a piece of rock assembled together. Aravalli, which is the oldest mountain range in the world, is also an ecosystem,” Jha said.

He warned that removing protection would open the area to massive damage not just from mining but also from real estate building. “Once we start calling it a forest and not a range, and it falls under a semi-urban landscape or rural landscape rather than a protected landscape, it will be open for any kind of exploitation through economic-commercial activity.”

What Gets Left Out

The new rules will exclude large areas that the Forest Survey of India previously identified as Aravalli. That scientific method counted all areas above a state’s lowest elevation that had slopes of at least three degrees. In Rajasthan, which holds nearly two-thirds of the mountain range, this meant areas above 115 meters with enough slope qualified as Aravalli.

Officials dropped several districts completely from the list of 34 Aravalli districts that span Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana and Delhi. Rajasthan’s Sawai Madhopur district, home to the famous Ranthambhore tiger reserve, no longer appears on the list. Chittorgarh district is also missing. This district has a UNESCO World Heritage fort built on Aravalli rocks. Nagaur district disappeared too, even though the Forest Survey found 1,110 square kilometers of Aravalli there.

The ministry told the Supreme Court it wanted to avoid “inclusion errors.” The committee said “not every part of the Aravalli is a Hill, and not every Hill is part of the Aravalli.” This thinking focuses on keeping non-Aravalli areas from getting protection. It does not focus on making sure all critical Aravalli areas get covered.

Environmental lawyers warn this approach could open large areas near Delhi-NCR for building projects. The Aravallis get much lower near the capital region. Most hilly areas there would no longer qualify as Aravalli under the 100-meter rule. This could turn these areas into prime land for construction.

Political Pushback Intensifies

Opposition parties have jumped into the fight. Senior Congress leader Jairam Ramesh served as Union Environment Minister before. He accused the government of “misleading the public” and forcing through a “fatally flawed” change. He said key groups opposed the new definition including the Forest Survey of India, the Central Empowered Committee of the Supreme Court, and the court’s own legal adviser.

“Why is the Modi Govt pushing through a fatally flawed redefinition of the Aravallis?” Ramesh asked on social media. He spoke to news agency ANI on December 24 and said the government was trying to “sell the Aravalli Hills instead of saving them.” Ramesh questioned whether the government’s 0.19 percent mining figure was honest. He noted this equals 68,000 acres of land.

“On what basis have they decided the 0.19 per cent of the Aravalli Hills? This is a game of figures. The environment should not be changed into a game of figures,” Ramesh said. He announced he will approach the Supreme Court in January to challenge the decision.

Samajwadi Party chief Akhilesh Yadav called the Aravallis “inseparable from Delhi’s survival.” Rajasthan Congress leader Tika Ram Jully called the range the state’s “lifeline.” He warned that without it, “the entire area up to Delhi would have turned into a desert.”

Protests Spread Across Region

Peaceful demonstrations have broken out in many cities. On December 21, hundreds of people walked silently in Gurugram under the Aravalli Bachao Citizens Movement banner. They carried signs reading “Save Aravalli Save Future” and “No Aravalli No Life.” The protesters marched toward the home of Haryana’s forest minister Rao Narbir Singh.

In Udaipur, lawyers protested outside courtrooms. Similar protests happened in Jaipur, Alwar, Faridabad, and other northern cities. Citizens, activists, farmers, and tribal groups organized human chains and silent marches. They raised concerns about dust storms, dropping groundwater levels, and worse air quality in Delhi-NCR.

Neelam Ahluwalia founded the People for Aravallis group. She told BBC the new definition threatens the range’s critical role in “preventing desertification, recharging groundwater and protecting livelihoods” in northwest India. Environmental activist Vikrant Tongad said countries around the world identify mountains and hill systems by what they do, not by random height limits.

“Any landform that is geologically part of the Aravalli system and plays a critical role in ecology or preventing desertification should be recognised as part of the range, regardless of its height,” Tongad told BBC.

Mining’s Long Shadow

Illegal mining has damaged the Aravalli range for decades even though the Supreme Court ordered it stopped many times. Since the 1980s, courts have stepped in repeatedly to stop uncontrolled digging in Rajasthan and Haryana. They cited damaged environment, air pollution, and health dangers. But enforcement stayed weak partly because operators could claim certain areas did not legally count as Aravalli.

A 2018 report by the Supreme Court’s Central Empowered Committee found that mining had already destroyed nearly 25 percent of Rajasthan’s Aravalli. News organizations including India Today documented how companies kept cutting hills in supposedly protected areas. JCB machines ran openly and people built farm houses on slopes.

Harjit Singh from the Sustainable Climate Foundation warned that “sustainable mining” on paper could mean roads, blasting, and pits cutting through animal paths and Delhi-NCR’s last green protection. Local activists say roads get built through hills first. Then people slowly take over land on both sides. Even when people complain, authorities rarely take action.

What Happens Next

The Supreme Court told the government to do thorough scientific mapping of the region and make clear management plans. Environmental lawyers say success depends on whether this mapping looks at water systems, plant and animal life, and land formations rather than just focusing on height.

Citizen groups demand that officials make maps and management plans public. They want independent scientists to review them. Without these protections, they argue the process will become just paperwork instead of real conservation.

The government says protected areas including tiger reserves, national parks, sanctuaries, special zones around these areas, wetlands, and plantation forests remain off-limits for mining no matter what the new definition says.

For now, India’s oldest mountain range faces an uncertain future. Whether the Supreme Court’s attempt to create clear rules helps or hurts environmental protection depends on what happens on the ground.

Climate problems get worse and water grows scarcer across northwest India. The fate of the Aravalli matters far beyond government boundaries and height measurements.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Small Wild Cats in Big Trouble: India’s First National Report Released

After Tragedy, Families Face Delays in Tiger Attack Compensation

Stay connected with Ground Report for underreported environmental stories.