Note – This is the second part of a two-part story series on solar energy’s integration in India’s wildlife conservation efforts. Click here to read the first part.

In the summer of May 2024, Mandar Pingle and other volunteers from the Satpuda Foundation hiked in the jungles of Pench Tiger Reserve, Maharashtra. They had a simple goal: carry the heavy equipment of an AI-based fire detection system to the highest point near the Kiringisara village located in the reserve’s buffer zone.

They did achieve the goal and installed the AI-based fire detection system, which runs on solar power.

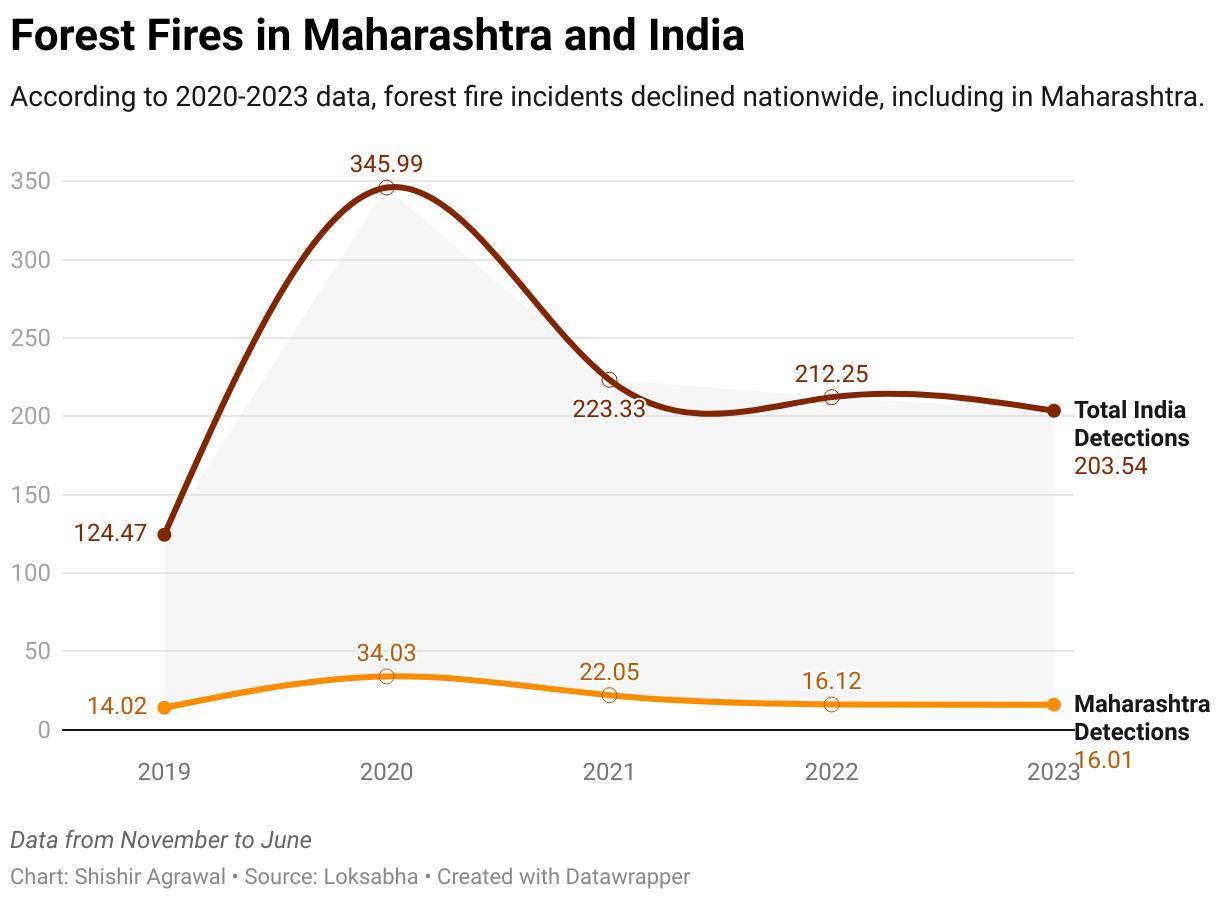

Rising temperatures and drier conditions driven by climate change are making forests increasingly prone to fire. Adding to the risk, villagers in surrounding areas sometimes burn crop residue, which can ignite uncontrollable flames. Almost 36% of India’s forest cover faces forest fires. In 2021, 659 hectares of the Pench, Maharashtra were destroyed in forest fires.

The unavailability of traditional power lines inside the protected forest makes installing and operating a fire-detection system a major challenge. And, Mandar Pingle, Deputy Director of the Satpura Foundation, sees solar power as what enables such an [AI-based fire detection] system to exist. It ensures continuous operation with battery assistance.

The mechanism, too, is quite simple. The system will detect the fire. The notification will be sent on a WhatsApp chat with exact coordinates to the nearby field staff. Then, the field staff has to verify the incident and send a photo to the same group. Using satellite data and camera feeds with a 15 km range, the system issues real-time alerts to the forest department’s field staff within just three minutes.

Pench, Maharashtra, is the first tiger reserve to install the system Pantera, developed by a Brazilian company called Umgraumeio, monitoring an area of just over 350 sq kms.

In the Pench Tiger Reserve, this solar-powered initiative is part of a broader effort to ease tensions between people and wildlife while protecting the forest from further degradation. In the reserve forest of India, mornings begin without the buzz of electricity. There are no streetlights, school bells, or hospital glow. Now, the same sun that feeds the forest is lighting it up in new ways. Solar panels power small ranger camps, charge radios, run water pumps, an early warning for fire detection, and a unique AI-enabled virtual wall system.

Mitigating Conflict Through AI, Powered by Solar

Almost 200 km from Pench is the Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve (TATR). Here, human-wildlife conflicts are common.

On September 24th, Amol Baban Nannavare (38), a resident of Bhamdeli village located in the buffer zone of this tiger reserve, died in a tiger attack. Nannavare worked as a gypsy (jeep) driver in the tiger reserve.

According to the 2022 census, Maharashtra’s Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve has 97 tigers. Human-tiger conflict is a major problem here. From 2005 to March 2020, 9,442 cases of human-wildlife conflict were recorded here, of which 58% (5,477) were human-tiger conflict cases. In the first 6 months of 2024, a total of 22 people were killed in tiger attacks in Maharashtra, of which 4 deaths occurred in the Tadoba Division alone.

To tackle this TATR, in April 2023, adopted an AI-based virtual wall system called Wildlife Eye. Till February 2025, 69 AI-enabled cameras were installed in 14 villages of Tadoba.

These cameras capture photos of animals through visual, thermal, and sound sensors. The data algorithms track the movement of each tiger by recognizing its stripe pattern and send alerts to local villagers and forest patrol teams when it approaches the settlements. Here, too, solar energy is used to power the system so it can operate in remote forest areas.

These cameras issued a total of 6,608 alerts, including 3,430 tiger alerts. And, in the same time period, there were no reported deaths in the villages with the virtual wall systems.

In August 2024, Maharashtra’s Pench Tiger Reserve installed six AI walls with a range of one kilometer in the Paoni range.

Solar ‘Solutions’ Bringing Change to Forest Staff Lives

On the other side, almost 450 km from Pench Tiger Reserve is Kheoni Wildlife Sanctuary in the Dewas district of Madhya Pradesh. Here, Krishnakant Verma has worked as a forest guard since 2012.

Verma walks approximately 20 km on foot daily, as part of his patrolling duties. His job is to monitor the forest area, prevent hunting attempts, extinguish and report fires, and inform the Range Officer in Kannod, 45 km away. Nowadays, he immediately sends a photo, video, or written message to his officers via WhatsApp. But almost ten years ago, he couldn’t do this.

Verma explains, “during the rainy season, we would park our vehicle 2-3 km ahead and walk to the camp.” Needless to say, there was no electricity. He says, “In the beginning, we would lock the room and cry about where we had come.” He says that his colleagues would tell Verma that he had received a posting at ‘Kala Paani‘– a colonial prison in the Andaman Islands known to be the most crucial punishment, mostly through isolation.

Until 2006-07, forest guards had only a dibri —a glass bottle filled with kerosene and lit with a cotton cloth wick. From 2007, the forest department gave them solar lanterns. In 2010, a 1 kW solar connection to their camps. “Now we are working on giving them 3 kW connections,” Rajnish Kumar Singh told Ground Report. He has been an Indian Forest Service officer since 1997, and is the Deputy Director of Pench Tiger Reserve.

With one torchlight and 15 liters of kerosene oil, Verma would patrol the forest and live for weeks. In those days, Verma had a keypad mobile phone. A single charge would last for days. But, “Once a week, a market would be held in the nearby village, and I would go there to buy necessary items and charge my mobile to talk to family members.” If, for some reason, he couldn’t go to the market, 15 days would pass before he could get news of his family.

And, information sharing with high officials would take five to six hours.

But in 2015, the forest department installed a 1-kilowatt solar electricity connection in his camp. We asked him, How much change has solar brought? “There has been a lot of change, sir; life has completely changed.”

Out of 250 government buildings in Pench Tiger Reserve, 175 rely entirely on solar power. We asked, under the RTI, how many forest offices in Madhya Pradesh’s tiger reserves and wildlife sanctuaries use solar energy. But the state’s forest department doesn’t collect or maintain such information.

Solar Pump Saves Labor and Time

Vijay Dgirve, a resident of Wagholi village near Sillari Gate of Pench Tiger Reserve, Maharashtra, 395.2 km away from Kheoni Wildlife Sanctuary, works as a Hungami Majur (seasonal forest laborer) with the forest department.

He also works with Pench’s Primary Response Team (PRT). In the summer, his main job is to ensure water availability inside the Tiger Reserve. Until 2019, he filled water holes built inside the reserve with hand pumps. Filling a single water hole would take at least five to six hours of pumping. This is a labour-intensive job. His other job is to reach villages where a tiger or other wild animal is spotted. He said that in the absence of PRT, people approach the tiger. This increases the risk of conflict.

The three-horsepower solar pump starts at seven am when the sun comes out. And, Dgirve turns it during his patrol visits. During summer days, since water consumption is higher, this pump runs for a longer time. Prabhunath Shukla, Deputy Director of Pench Maharashtra, says that about 150 water holes in the Tiger Reserve are completely operated by solar pumps.

About 80 such solar pumps are also installed in the Pench Tiger Reserve of Madhya Pradesh. Singh says that earlier during summers, water had to be supplied manually through hand pumps or by taking tankers via tractors. The noise from tractors and human activity disturbs wild animals.

There are smaller inclusions, like radio collars to track animals and birds as well. Manan Mahadev, who works on vulture conservation at Bombay Natural History Society, says that solar energy fulfills his needs. The vultures that he releases in the wild travel long distances. Solar panels/plates provide the collar with continuous power.

The Maharashtra Government wants the Pench Tiger Reserve to run completely on solar energy. They launched a 2.50 crore project in May 2023.

The decentralised nature of solar energy gives the forest department the freedom to experiment and use it in different aspects of conservation. The eagerness is palpable, but there are constraints on finances. Even the AI-detection system or virtual walls were installed with the support of Satpuda Foundation. PwC India Foundation installed solar panels in nine remote forest outposts in Kanha National Park, approximately 200 km from Pench.

Solar energy is playing a major role in everything from saving forests and animals from fire to protecting humans from animals. The transformation that has come in the lives of Forest Guards – the smallest but most important unit of the Forest Department – is as significant as the arrival of electricity in a village.

While talking to us, Forest Department officials also acknowledge that the government should increase the budget to implement these conservation measures at the tiger reserve level. It is necessary for Madhya Pradesh that the state government creates a plan at its level to promote the role of solar energy in forest conservation, and at the same time, learning from its neighboring states, measures like AI fire detection systems should also be adopted in this state.

This story was produced with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Tiger. Man. Man-eater Tiger. What or Who Turns Them Man-eater?

After Tragedy, Families Face Delays in Tiger Attack Compensation

Stay connected with Ground Report for underreported environmental stories.

Follow us onX, Instagram, and Facebook; share your thoughts at greport2018@gmail.com; subscribe to our weekly newsletter for deep dives from the margins; join ourWhatsApp community for real-time updates; and catch our video reports on YouTube.

Your support amplifies voices too often overlooked, thank you for being part of the movement.