On the evening of August 11, 2024, in Pench Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh, routine cattle grazing turned almost deadly for Balakram. He guided the livestock to the tropical moist deciduous forest in the buffer zones of the tiger reserve. These are familiar fields, though sometimes, around 4:30 PM, while managing his cattle herd, he turned around to see one of nature’s most powerful predators, a Bengal tiger, launching towards him.

He remembers a thunderous roar and the tiger pouncing on him. He fell on the ground with his face towards the sky. The tiger tried to grab him, almost hurting his face, ripping his cheek, throat, and damaging his eye. In that split second, Balakram’s survival instincts kicked in. “I grabbed his claws with both my hands and held on with all my strength,” he recalled. “I held on tight and then suddenly lifted the tiger and threw it away. After that, it [the tiger] ran away.” He doesn’t know how he gathered all that strength to throw away a 300 kg beast, though he repeatedly thanked God for saving his life.

The tiger’s roar dispersed the cattle. His companion, Sarif, some feet away, had also heard the roar. He came towards him. The local community from nearby villages was already gathered together for the closing ceremony of a religious event at the village temple. As they alerted the villagers of the attack, they came to the forest.

Villagers put injured Balkram into a vehicle and immediately contacted forest officials. The Pench Tiger Reserve’s ranger arrived in a car and transported Balakram to a hospital in Kurai. The encounter lasted minutes, but the damage was severe. The tiger’s claws and teeth left deep wounds across his face, head, and eye. His cheek was torn open, and he suffered multiple lacerations that would require extensive medical treatment. From there, he was referred to Nagpur, a major city nearby, for specialised treatment.

He spent 15 days in the hospital, with 11 days in the intensive care unit. The tiger’s attack had caused severe facial injuries, including a completely shattered cheekbone that required surgical reconstruction. Doctors performed multiple surgeries, installing metal plates to repair the damaged bone structure. A metal plate runs from the right side of his nose across his left cheek.

Since the incident, he hasn’t been able to open one of his eyes and wears sunglasses. The medical expenses were substantial— approximately ₹5.5 lakh. The forest department covered ₹3.5 lakh of the hospital bills; his family had to bear the remaining costs.

This is not the only incident. On June 20, 2025, an 18-year-old youth, Sumit Pandre, was killed by a tiger in Seoni district’s buffer zone. Earlier, on October 17, 2024, a farmer was killed in the Paoni range of the buffer zone in Pench Tiger Reserve. He became the 11th victim of tiger attacks in just four years. Each death fuels more distrust. Crowds have gathered, often clashing with forest officials.

Though, despite the horrific injuries, Balakram had done the seemingly impossible – he had survived a confrontation with a tiger.

Rising Human-Tiger Conflict

Balakram’s survival story should be understood against the backdrop of human-wildlife conflict, generally in India, and particularly in the Pench Tiger Reserve region. Pench Tiger Reserve has two regions: Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra

Between 2019-2024, 395 humans have died in conflict with tigers, as per a response in the parliament. The year 2022 saw the deaths rise by more than 100, to 110. The bulk of these deaths have come just in Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, with Maharashtra accounting for four out of every ten tiger-human conflict-related deaths.

Human deaths are a conflict’s one aspect. Injuries in the case of Balakram are another aspect. Then, there are cattle-killings and crop damage. Apart from this, the constant fear that restricts locals’ movement in their own villages and agricultural fields.

When asked about the increase, villagers offer their own explanations. Some point to a rise in the tiger population, others to the aggression of the mating season. Many note that the big cats’ natural prey—spotted deer—were relocated to Kuno National Park in Sheopur, in North Madhya Pradesh, for the cheetahs reintroduced there. And then there is the new, eight-kilometre, four-lane highway that cuts across the landscape. Its underpasses are intended for safe passage, but locals said they increase predators’ movement.

In another theory, the local said the forest department is releasing new tigers. Why would the forest department do this? I asked them. They didn’t know. The encounter did reflect a lack of trust or synergy between the forest department and the villagers. But, villagers, in their own words, were pointing to India’s great conservation achievement and increase in tiger population.

India is home to 3,682 wild tigers as of 2025– 75% of the world’s wild tiger population.

The Tiger Population Boom

In some ways, India’s conservation success story is the reason behind the increased conflict. Take, for instance, Madhya Pradesh, the state with nine tiger reserves— Kanha, Bandhavgarh, Pench, Satpura, Panna, Sanjay-Dubri, Ratapani, Veerangana Durgavati, and Madhav– also has the largest tiger population.

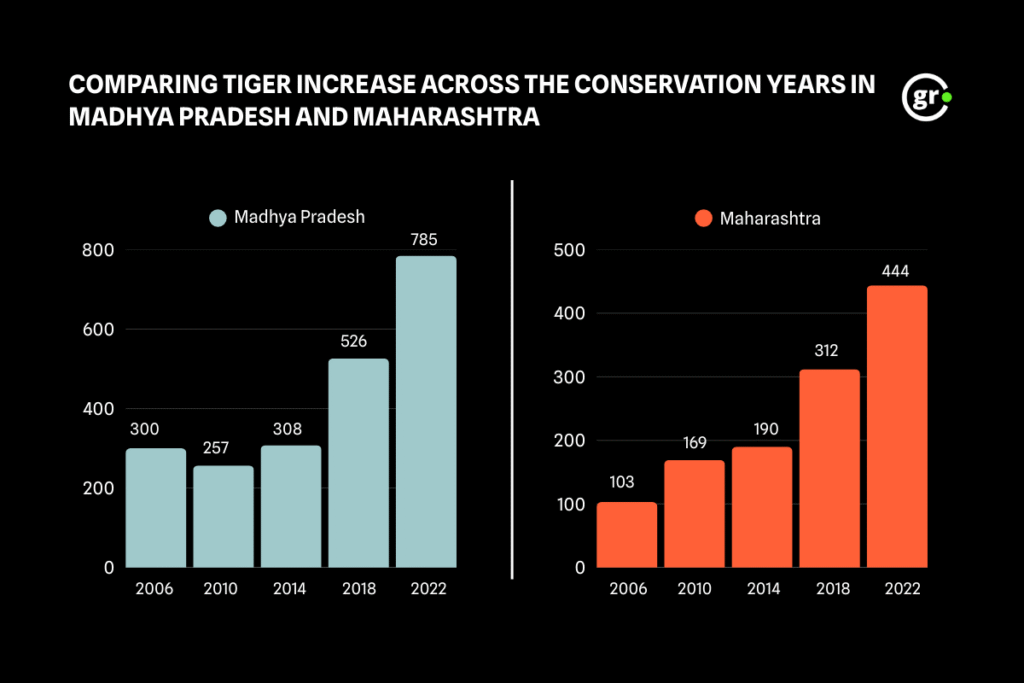

The table below shows the increase in the tiger population between Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra since the beginning of tiger conservation projects.

The buffer zone of Pench Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh covers a total of 108 villages, as recorded in the Eco-Sensitive Zone notification. On the Maharashtra side, the Pench buffer includes 63 villages, as listed in the Eco-Sensitive Zone notification. A total of 171 human-inhabited villages. The cattle in the village become easy prey for young tigers. Cattle don’t run as fast as a spotted deer, and in the village set-up, are often tied.

The Pench Madhya Pradesh section has over 70 tigers in the forest core area of 411.330 sq.km. And, there are 51 tigers in Maharashtra, based census conducted in 2023-2024, with the estimated tiger density of about 8 tigers per 100 sq. km. Most of these tigers are limited to the core area, but some wander in the buffer zones too. Here, they interact with the villagers, cattle, and the agricultural fields.

Mandar Pingle, Deputy Director of Satpuda Foundation, explained: “In Pench, the tiger density is around 10 to 12. That means each tiger requires roughly 10 to 12 square kilometres of space. With this kind of density, competition is natural, and younger tigers get pushed out towards buffer areas.” A male tiger’s territory can be 40 to 60 square kilometres, while a tigress may use around 20 to 25.

The availability of food, water, and safety determined their movement. If not, they start moving vast distances in search of new areas.

The shrinking interface between wild habitats and human settlements exacerbated the conflict. “Farmers have started cultivating every available piece of land… so farmers inevitably take cattle into the core forest area for grazing,” said Deputy Director of Pench Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh, Rajnish Kumar Singh. The traditional grazing areas are converted into agricultural land.

“Earlier, there were dedicated pasture lands for cattle grazing. In Maharashtra, these were called gayran. With encroachment and overgrazing, fodder is gone. Now villagers take cattle deeper into forests, which increases negative interactions with tigers,” said Pingle.

Overcrowded forests, blocked corridors, and croplands near reserves fuel conflict.

The Role of Wildlife Corridors

In some ways, villagers’ concerns and reasoning are true. With an increased tiger population, there is a lack of prey, and the density is too high for tigers to live in the region. But, how do they move around? The tigers need to naturally or organically travel to a different forest. The forest department can’t just move the tiger from one tiger reserve to another. Rajnish Singh laughed at this suggestion and explained that a change in habitat without the wild animals’ own volition impacts how they function in that habitat. This can disrupt their behaviour, health, and survival.

The well-connected patches and wildlife corridors are vital “in maintaining genetic diversity, reducing human-wildlife conflict, and ensuring the long-term survival of tiger populations.”

“..When historical corridors are blocked by highways, railways, canals, or agriculture, dispersal turns into conflict,” Pingle said.

“It has become crucial to ensure well-connected forest patches that allow their free movement across landscapes,” said Swati Saini. She was one of the authors of the 2014 study titled: Connecting Tiger Populations for Long-term Conservation. This was the first of his efforts to “identify potential connectivity linkages and ecological bottlenecks across tiger landscapes in the country.”

“From Pench to Kanha, around four weak links/bottlenecks are there, that are crucial to address. From Pench–Satpura–Melghat tiger reserves, around 8-9 places are more fragmented and weak links,” explained Saini.

“The entire corridor is under pressure because of various human activities, livestock grazing, and developmental expansion. The growth in human population and tourism around the two tiger reserves has also exacerbated the cases of human–wildlife conflict; therefore, local coordination matters a lot for conservation of this connectivity,” Saini said.

Conservation Efforts and Challenges

Singh mentioned how we as humans have to manage our lives around tigers. We can’t expect tigers to understand the society we have built. He reassured that tigers don’t kill or attack humans unless they are themselves threatened. “The term ‘man-eater’ comes from the British era. I prefer ‘problem tiger,’” Pingle said. “In rare cases, injured or old tigers may habitually attack humans. But in most incidents, people come between a tiger and its cattle prey. That’s when tragedy happens.” And, Pingle said, “When herders intervene with sticks or axes, attacks on people occur. Most cases are not about ‘man-eaters’ but about survival.”

He said that spotting a tiger isn’t a conflict. But we tend to feed into our fascination for this majestic beast. We make videos and gather a crowd around him. That can intimidate the tiger, he explained.

The Pench Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh has implemented several initiatives. The reserve has launched the “Sayane Mowgli ki Cycle” program, where forest workers ride bicycles through buffer zone villages to spread awareness about tiger movement and safety measures.

Several technological and policy interventions are being implemented to reduce human-tiger conflict. Solar-powered fencing systems have been installed, though coverage remains limited. Early warning systems using camera traps and mobile technology are being developed to alert communities when tigers are detected near villages.

But a lot more has to be done in terms of having free movement of animals, particularly tigers, between forests. Even Singh agreed with the limitations.

Life After the Attack

More than eleven months after the attack, a tall, almost six-foot man walks into the compound of his house. With his stature, black sunglasses, and orange loincloth (absorbent cotton cloth), in overcast weather, one can barely assume that Balakram survived a tiger attack. A feat very few people can boast of. If villagers are to be believed, he is the only one in the entire village to do so.

Though he continues to grapple with its physical and psychological aftermath. He can no longer run or perform heavy physical labour as he once did. “Fear definitely comes when going to the forest,” he admitted. “When I’m alone and remember what I witnessed, my body trembles.” He reduced his cattle herd from 15 to 11 animals and has had to invest in purchased fodder rather than free forest grazing. He now spends ₹7,000 annually on wheat chaff alone. Despite this trauma, economic necessity forces him to sometimes take his reduced livestock herd for grazing near the forest.

Even after suffering life-altering injuries, he was not eligible for disability compensation because medical authorities determined he was not technically disabled. While he received ₹3.5 lakh in medical coverage from the forest department, he still faces ongoing medical expenses. Doctors recommend removing the metal plates from his face, an operation that would cost approximately ₹1.5 lakh.

In a separate article, we talked about the compensation dilemma in the state of Madhya Pradesh. The Chief Minister Mohan Yadav announced 25 lakhs, an increase from the earlier 8 lakhs, to the family of the deceased in the tiger attack. This is what the adjacent state of Maharashtra also compensates. However, there wasn’t any official notification to mandate this. So, when a young boy died and was just compensated 8 lakhs, the villagers protested.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Small Wild Cats in Big Trouble: India’s First National Report Released

After Tragedy, Families Face Delays in Tiger Attack Compensation

Stay connected with Ground Report for underreported environmental stories.

Follow us onX, Instagram, and Facebook; share your thoughts at greport2018@gmail.com; subscribe to our weekly newsletter for deep dives from the margins; join our WhatsApp community for real-time updates; and catch our video reports on YouTube.

Your support amplifies voices too often overlooked, thank you for being part of the movement.