The Indira Sagar Dam, built on the Narmada River, is known for having the highest storage capacity in the country. This multipurpose project with a storage capacity of 12.22 billion cubic meters (BMC) was designed to generate electricity with a total installed capacity of 1000 megawatts and provide annual irrigation facilities to a total of 1.69 lakh hectares of land in Khargone, Khandwa, and Barwani districts. The main canal of this dam is 249 km long, of which an 89 km long canal passes through the Barwani district.

While this canal has benefited many farmers on one hand, irregularities in canal maintenance have also caused losses to many cultivators on the other. Field visits to villages across Barwani district reveal gaps between government claims and the ground realities of the canal project’s implementation.

Year-Round Farming

In Barwani district, the Indira Sagar main canal enters from Thikri, located on the eastern border of the district, and ends at village Palya, passing through various villages of Rajpur, Anjad, and Barwani development blocks.

Gautam Chauhan farms 2.5 acres in Village Palya, located at the end of the Indira Sagar canal in Barwani block. Five years ago, he could only grow crops during the monsoon season and left his fields empty during the rabi season. Now, canal water allows him to grow wheat in the rabi season, giving him two crops per year instead of one.

Earlier, Chauhan’s field didn’t have an electricity pole, so he couldn’t bring water from other fields through motors for irrigation. But after the canal arrived, he irrigated using the siphon technique. For this, he has to immerse his pipe in the canal, then by applying slight pressure and pulling from the other end of the pipe, water starts flowing from the higher level to the lower level.

Chauhan is not the only beneficiary. Raisingh from Badgaon, who farms 2 acres, has seen similar gains. He previously grew crops only during monsoons, but canal water now lets him grow cotton in the kharif season and wheat in the rabi season.

But water access is uneven. Sahda, who farms 1.5 acres in the same village as Raisingh, gets no benefit from the canal. His fields sit higher than the canal, making it impossible to use siphon irrigation. Without a motor pump or electricity, he still relies only on monsoon rains for farming.

Ignored Complaints

Vikram, a farmer from Kari village, grows two crops a year with canal irrigation. But he is unhappy that the department neither cleans the canals nor repairs damage. He shares that the farmers have to clean the canals around their fields and fix minor damage themselves.

Farmer Hemraj Malviya from Thikri tehsil complained about canal damage on the CM helpline last year, but his complaint was closed without any action. This wasn’t his first attempt – he had raised the same issue at the collector’s public hearing before, but officials dismissed it, citing lack of funds without even visiting the site. Malviya questions the canal’s construction quality, saying the smaller canals broke before they could even be used.

Canal systems work in stages: water flows from the main canal to branch canals, then to smaller distributary canals and minors, and finally through sub-minors that carry water directly to farmers’ fields.

Rahul Khachra, a large-scale farmer, lost money instead of gaining from the canal. He recalls June 23, 2024, when the minor canal near his field broke during the season’s first rainfall. The breach flooded his cotton and chili crops, destroying his entire harvest.

It has been a year since this incident, but this canal is still broken. Rahul said that when he complained to the collector’s public hearing and CM helpline for canal repair, the officials instead accused him of damaging the canal. Finally, giving up hope for canal repair, the farmer had to spend his own money to raise his field’s bunds to save his farming. Rahul said that canals are never cleaned; last year he had to spend ₹11,500 for cleaning to bring water to his field.

Another farmer from Talun, Dharmesh Nagor, says that crops in his field get damaged due to seepage from the canal, but officials are not solving his problem. This farmer says that seepage drains have not been built parallel to the canals, so when water overflows, it fills his fields. In most places, these canals have been damaged for years, and no attention has been paid to their improvement.

Jalal Bhai, a resident of Devjhiri Falya in village Mandil of Rajpur tehsil, has a different problem. Some of his land was acquired for the canal. During construction, debris from canal excavation was dumped on his remaining land. When he complained, he was given a very irresponsible answer that the contractor didn’t know the land belonged to him.

Jalal had bought this land with compensation money from his land acquired for the canal. After repeated complaints, officials came to the site and assured debris removal, but only a little debris was removed. He had to get the rest of the debris removed himself. Until all debris was removed from the field, farming couldn’t be done there.

Rama from Pichhodi village lost his farmland to the Sardar Sarovar Dam project. He used his compensation money to buy new land in Mandil and Nandgaon villages. But those fields were also taken for the Indira Sagar canal. Even on his remaining land, construction crews dumped canal debris. Though he struggled to clear most of it, debris pieces still lie scattered across his field.

Mahadev Patidar of village Kuan (Tehsil Thikri) has been left with more than 50 meters of unlined canal section in his field located in Brahmin village. Due to lack of cleaning, bushes have grown around the canal, making it difficult to even locate the canal. Not only this, but the canal has been brought into his field and abandoned there. At the terminal end of the canal, the remaining unused water, along with silt, has filled up the well in his field. The motor and pipes installed at the well have been buried under the silt that came with the water. His complaints over the past 2 years have yielded no results.

Taking us to his second field, located between village Kuan and Kerwa, he showed that the road that was supposed to be built alongside the canal has not been constructed. Due to this, during the rains, the mud makes it extremely difficult for both livestock and humans to walk. Since vehicles cannot reach the fields, farmers are forced to carry cattle fodder on their heads.

Farmer Committees Without Farmers

From 1961 to 1980, the government spent heavily on major irrigation projects across India, including Madhya Pradesh. But poor canal management after construction made these projects fail to meet their goals. To fix this problem, water user committees were created to involve farmers in managing irrigation systems.

Under the Madhya Pradesh Sinchai Prabandhan me Krishkon ki Bhagidari Adhiniyam, 1999, water user committees should handle canal maintenance and management. Seven such committees were formed for Barwani’s 14,544 hectares of irrigated land. Ground Report spoke with presidents of six committees – Mohipura, Palasya, Talwada Buzurg, Borlay, Kari, and Kalyanpura. The law requires these committees to collect fees from farmers and use the money for canal repairs. But the committee presidents themselves admit their groups exist only on paper.

Most committees don’t even have receipt books to collect fees. Even where receipts exist, the actual collections remain minimal.

Rajendra Singh, president of Mohipura Water User Institution, said that in their area, 90 percent of farmers’ lands are already irrigated by private Narmada pipelines, but proper irrigation facilities are not being provided to the remaining 10 percent of farmers either.

Gautam Chauhan from Palya village said that farmers do minor cleaning around their fields themselves, but no one cleans the silt inside the canals. Sub-divisional officer R.S. Dharve also admits that due to a lack of budget, canals have not been cleaned for the past 6-7 years. On the question of canal repairs, he admits that the work hasn’t been done for the past 10 years.

Revenue Collection Fails

By February 2012, the dam irrigated only 41,727 hectares against its annual target of 1.69 lakh hectares. Sub-divisional officer R.S. Dharve explains the current situation in Barwani:

“Our target was to irrigate 19,600 hectares. We achieved 14,544 hectares. The remaining work has been stopped permanently because farmers opposed it and we couldn’t acquire more land. No further construction will happen.”

With the state government providing no separate repair budget, canal maintenance depends entirely on irrigation fees collected from farmers. But department records show fee collection is also very poor.

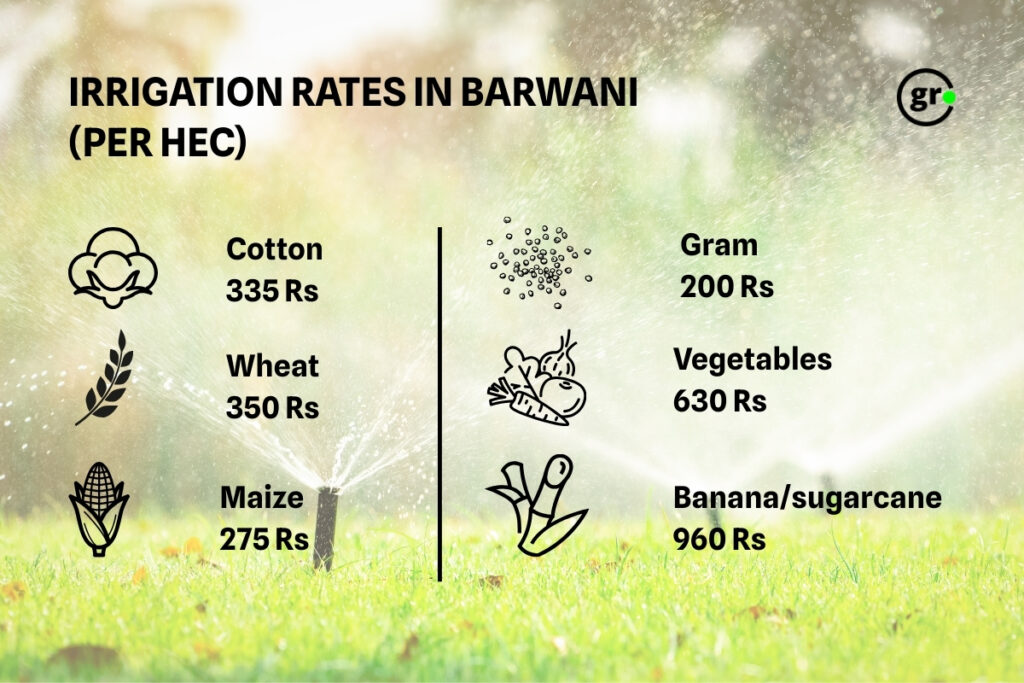

By the department under the Barwani sub-division, revenue collection in the last financial year 2024-25 was only ₹4,09,000, i.e., about ₹26 per hectare of irrigation. While in this area, mostly the cotton (kharif) and wheat (rabi) crop cycle is prevalent. The annual revenue for both these crops is ₹685. Looking at it this way, revenue collection is less than even 4 percent.

However, the situation of revenue collection at the state level is not very different from this. In Madhya Pradesh, which claims to have irrigated 50 lakh hectares by the end of 2024, revenue collection in the financial year 2024-25 was only ₹35.43 crores. In the previous financial years 2022-23 and 2023-24, ₹45.58 crores and ₹36.98 crores, respectively, were collected as revenue.

Since officials themselves have said that no further canal construction will be done, only the management of existing canals can save the Indira Sagar project from failure. But our investigation makes it clear that the condition of the canals is very poor. Rajendra Singh, president of Mohipura Water User Institution, calling the canal construction quality poor, said that if even a cat scratches these canals, they would break. The state of disorder is such that even the gate valves that open and close the canals have been stolen.

The deteriorating infrastructure reflects years of systematic neglect and inadequate investment in maintenance. With no dedicated budget allocation for repairs and cleaning operations suspended for over six years, the canal network has become more of a liability than an asset. The irony is stark – a project designed to transform agricultural productivity has instead become a source of flooding, crop destruction, and financial burden for the very farmers it was meant to serve.

The absence of proper drainage systems, combined with structural failures and administrative apathy, has created a vicious cycle where farmers must either abandon their fields or spend their resources to mitigate damage caused by the faulty canal system. In this situation, it would not be wrong to say that these canals have caused losses to farmers rather than benefits.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

The Narmada Valley Development Project: A Never-Ending Controversy

Narmada Bachao Andolan completed 40 years of struggle

Costliest water from Narmada is putting financial burden on Indore

Bhopal failing its river, impacting Narmada’s ecology and river system

Stay connected with Ground Report for underreported environmental stories.

Follow us onX, Instagram, and Facebook; share your thoughts at greport2018@gmail.com; subscribe to our weekly newsletter for deep dives from the margins; join ourWhatsApp communityfor real-time updates; and catch our video reports on YouTube.

Your support amplifies voices too often overlooked—thank you for being part of the movement.