Balram Chandravanshi, Narayan Chandravanshi, and Sanju Kahar share the same address– Village Bhula, Panchayat Bhula, Tehsil Chhindwara, District Chhindwara. An underwater village submerged in 2017 by the backwaters of the Machagora Dam, part of the Pench Diversion Project.

इस बीच मेरा शहर एक विशालकाय बांध के पानी में डूब गया

उसके बदले वैसा ही एक और शहर उठा दिया गया

लेकिन मैंने कहा यह वह नहीं है मेरा शहर एक खालीपन है

Meanwhile, my city was drowned in the waters of a gigantic dam

In its place, another city just like it was raised

But I said: this is not it—my city is an emptiness.

“बची हुई जगहें” (Remaining Places) by Manglesh Dabral

On August 13, 2025, as rain poured down, Narayan stood under the veranda of a locked house and recalled what had happened a decade ago. In 2014, the state’s Irrigation Department informed him along with the rest of the village that by the next July, their homes and fields would be underwater.

In May and June of 2015, despite their protests and under the police watch, Narayan and other villagers were relocated to a government rehabilitation site, in Jamunia, 15 km from the Chhindwara district headquarters. “We had never seen this place before,” he said. “When we came here, it was raining just like this. No electricity, no road, and no water, only 40×60 square feet plots marked out for us.”

For several days, Narayan lived in a tarpaulin tent with his nine-member family and fetched drinking water. He built a house with his savings and compensation money. But, continued to struggle for employment, drinking water, and education for his children.

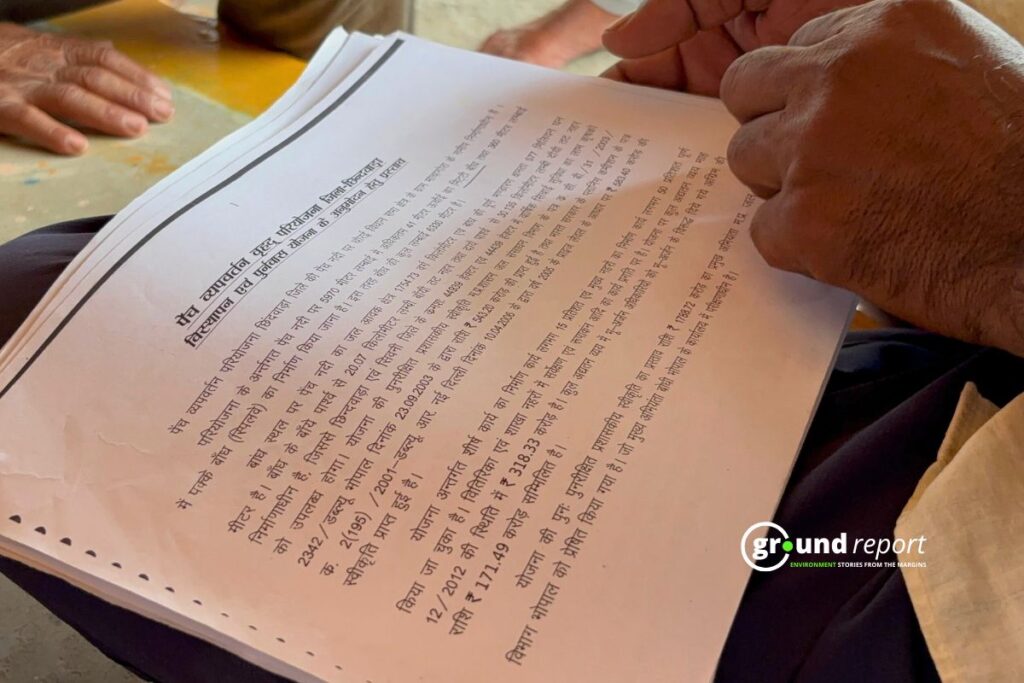

Ground Report reviewed official documents on the project’s rehabilitation process and visited resettlement sites to understand the ground reality. The objective of Madhya Pradesh Adarsh Punarwas Niti 2002 is that the displaced families should regain their previous standard of living in the new place as soon as possible and also improve it within a reasonable time. Through this investigation we wanted to have answers to two simple questions: how are the displaced families living now, and what is their standard of living like?

Life After Displacement: Paper vs Reality

Started in 1987-88, the Pench Diversion Project’s goal was to divert water from the sub-basin of the Pench River, a tributary of the Godavari River, to the sub-basin of the Wainganga River. For this, a 5.97 km long and 42 meter high earthen dam and a 360 meter long and 46.5 meter high concrete dam were constructed. The project promised big benefits of irrigation for 85,000 hectares of farmland and 7.40 million cubic meters of drinking water in Chhindwara and Seoni districts.

In April 1988, the Madhya Pradesh government approved ₹91.60 crore for the project, but by 2017, the cost had ballooned to ₹2,544.57 crore. Though these numbers mean little to Narayan Chandravanshi, and his 18 acres of land: all swallowed by the dam’s backwaters.

His land was part of 6502.68 hectares of land submerged in the Project. Four of the 35 affected villages (Dhanora, Barahbariyari, Bhutera, and Bhula Mohgaon) were completely submerged. While 13 villages were partially affected, only the agricultural land of 18 villages was submerged. Eight different rehabilitation sites were established to accommodate the displaced communities.

Protesting villagers and social workers want the rehabilitation as per the Madhya Pradesh Adarsh Punarwas Niti 2002. But, how can a project approved in 1987 follow the 2002 rehabilitation policy?

“Even though the project was approved in 1987, the work of building the dam started from November 4, 2012… Land acquisition awards were passed from 2006 to 2016. Therefore, rehabilitation should be done under the 2002 policy,” explained advocate and social worker Aradhana Bhargav. She is fighting a legal battle in the Supreme Court, seeking proper rehabilitation for those displaced by the project.

The letter, accessed by Ground Report, by the Additional Secretary of Madhya Pradesh Water Resources Department to the Chhindwara Collector aligned with Bhargav’s explanation. The letter mentioned that 660.80 hectares of land in Bhutera, Machagora, and Bamhanwada villages were indeed acquired in 2006 and 2009, decades after project approval.

Aradhana Bhargav has been fighting a legal battle in the Supreme Court since 2013 against all irregularities in compensation and rehabilitation. Apart from her, four other individuals, including Narmada Bachao Andolan leader Medha Patkar, are petitioners in this case.

According to the Madhya Pradesh’s 2002 Model Rehabilitation Policy, “Any member of an affected family who is 18 years or older on a specified date mentioned in the development plan will be considered a partner as an independent family for participation in the project’s economic activities and rehabilitation benefits.”

During Narayan’s family’s rehabilitation, his three brothers and mother got land leases. Though, both his sisters are yet to receive leases. Similarly, Balram Chandravanshi’s three daughters were also of age in 2016, but have not received their land leases either.

The project affected some villages, and the authorities paid very little compensation for the acquired land. Bhargav said that land acquisition awards for Bhutera, Machagora, and Bamanwada were passed in 2007. The mentioned compensation ranges from 3000 rupees to 9000 rupees per acre. Bhargav raised some important questions.

The policy guides the price of their land equal to the price of land in the command area. “While determining compensation for agricultural land and rural population plots proposed for acquisition under the project, the land prices of nearby irrigated (command) areas will be taken as the basis.”

However, according to the proposal prepared for this project, the compensation rates are to be given in accordance with the provisions laid down in the Land Acquisition Act 2002, based on whichever is higher the sale deeds of the same village or the collector guideline rates of the year of publication under Section 4.

But for Narayan and Balram, to all villagers, the compensation amount was fixed based on the land price in their submergence area. Bhargav explained this in more detail,

“When it was decided in 1987 which villages would be submerged by the dam, obviously, no one would buy land in that place. As a result, the price of land in all villages like Bhula did not increase even by 2007. The price of land around which canals were to come (the command area), naturally increased. While fixing compensation, the rate of this command area per acre should have been the basis.”

“It Broke My Morale”

“Coming here completely broke my morale,” Narayan said. His family’s profession was farming, so as per the policy, he should have been settled in the command area—lands irrigated by the canals. This would have allowed Narayan and his family to continue farming and earn their livelihood. The simplest course would have been to acquire Narayan’s farm alongside the project and set aside land in the command area for resettlement. That, however, never happened.

In the rehabilitation proposal prepared by the Chief Engineer of the Baineganga Basin Water Resources Department, Seoni, stated, ‘it is currently not possible to acquire 50% land in the command area and make it available to submergence-affected farmers.’ While Supervision Engineer Kaurav Patel of the Water Resources Department admitted that there is no plan to give land to these farmers in the command area in the future.

As a result, Narayan travels to Chhindwara to work as a laborer. He leaves home at 8 o’clock, and often returns empty-handed in the evening. Others also face more or less the same situation. Balram Chandravanshi, another villager from Bhula Rehabilitation, said, “Here we have been confined in 40×60 plots in such a way that we can neither live nor do anything.”

The rain intensity increased. We took refuge under the ledge of a locked house. The villagers told us that the owner had migrated to Chhindwara to earn a living.

Women Left Out of Decisions

Aradhana Bhargav, the only woman in the gathering, addressed an organized meeting at the Bhula Rehabilitation site under the banner of Kisan Sangharsh Samiti. Bhargav explained the 2002 policy and what their rights are as displaced individuals.

Shivkali (65), who gives only her first name, used to farm on five acres of land in Dhanora. Getting up early in the morning, doing all the household work, cooking food, and then going to the fields – this was her daily routine. But her farm, too, was submerged. How much compensation did she get for this? In response to this question, she said, amused, “The elders would know; we don’t know. After all we are Bahu-beti only.”

Similarly, Sanju Kahar (38) has a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree. But her life is centred around her 14-member joint family, and her four children. Her husband runs a small shop, and Sanju works as a laborer in nearby fields. However, Sanju is concerned about her children’s safety. She tried settling 10 km away in Singori, but the lack of adequate bus facilities got her back to Bhula. The future of her children looks bleak to her, she admitted.

There are incidents of crimes against women and thefts, but the police would not register any complaints. Villages said that the complexity is in the jurisdiction; Bhula doesn’t come under the Singori police station or the Chhindwara police station. However, Sub Inspector Avinash Pardhi informed that the Bhula Rehabilitation site comes under the Dharm Tekri police station, where villagers can register their complaints.

Committee Yet to Visit Villages

In September 2022, the court asked the Madhya Pradesh government about the rehabilitation of project-affected people. After the report filed by the state government, while hearing this case on March 19, 2025, the bench of Justice Abhay S. Oka and Justice Ujjal Bhuyan ordered the formation of a fact-finding committee in the case.

In its order dated April 17, 2025, the court has constituted a seven-member committee, which includes the Secretary of Madhya Pradesh Water Resources Department and the Commissioner of Jabalpur Revenue Department. This committee, apart from government documents, will also visit all eight rehabilitation sites, including Bhula, to see what condition these villagers are living in after displacement.

The committee has to present its report to the court in six months. Though, at least till August 2025, three months after the court’s order, no such team has visited Bhula. Bhargav said that if this team does not present a report within six months, a case of contempt of court can be made against them.

The documents submitted to the Supreme Court state that a total of 1,752 plots were made available across eight rehabilitation sites for villages affected by the project. Of these, 1,579 plots have been allotted to displaced families, while 969 families opted to receive compensation grants instead of plots. A total of 10.52 million rupees has been disbursed to these families in grants.

At the Jamuniya Maduadhana (Bhula) rehabilitation site, 392 of the 444 plots have been allocated. Numerous parcels are vacant as many families, however, are yet to begin construction on their allotted plots. Local residents reported that soil from some of these plots has been dug up by land mafias, leaving large pits behind. Some affected landowners have filed formal complaints requesting replacement plots, copies of which are on record.

Multiple attempts to reach the local SDM for an official response were unsuccessful. We will update the report when we get a response.

Residents of the another, Dhanora-Barahbariyar rehabilitation site rely on hand pumps and backwater from the dam for drinking water. A water treatment system with a capacity of 3,000 liters was installed to serve the village. When our team visited on August 13th, the system was not operational. Water samples were collected and results will be updated once available.

The 2002 rehabilitation policy is the state’s model rehabilitation policy, which was also used as a reference for the National Rehabilitation and Resettlement Policy of 2007. But any policy, if not followed, remains ideal only on paper. Looking at Bhula and all other rehabilitation sites, it is understood that the government conceived a project, displaced people, made a policy, and then forgot both the village and the policy.

That’s why these villagers are still searching for the meaning of their lives today.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Indira Sagar Canal Mismanagement Hurts Barwani Farmers

Water for power plant, but none for people, story of displaced farmers

Stay connected with Ground Report for underreported environmental stories.

Follow us on X, Instagram, and Facebook; share your thoughts at greport2018@gmail.com; subscribe to our weekly newsletter for deep dives from the margins; join our WhatsApp community for real-time updates; and catch our video reports on YouTube.

Your support amplifies voices too often overlooked, thank you for being part of the movement.