The Union Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change has notified new Solid Waste Management Rules. These rules will replace the 2016 rules and will come into force from April 1, 2026. The new rules expand polluters responsibility and make source-level segregation of waste more stringent and systematic. Government offices, public sector undertakings, and even private residential colonies have been made accountable for the solid waste they generate.

Now, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) will issue detailed guidelines under these rules. The responsibility of recovering compensation for violations will lie with the State Pollution Control Boards (SPCB) and Pollution Control Committees (PCC).

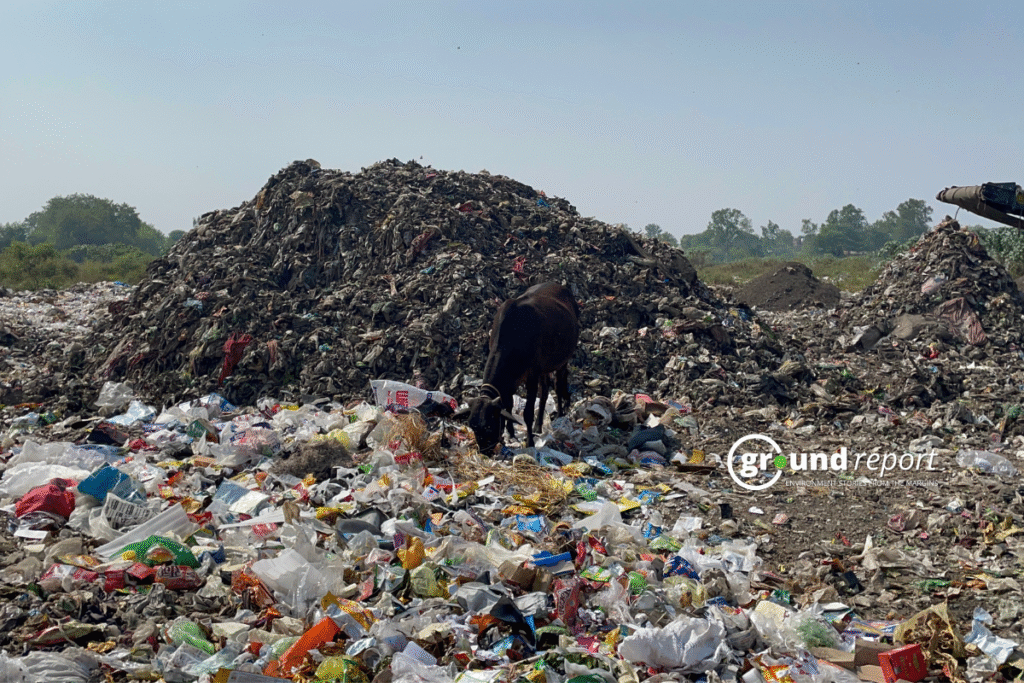

In this context, it is important to assess Bhopal’s preparedness for the new rules and the gaps in the city’s solid waste management system need urgent attention.

Solid waste generation in Bhopal

In the latest Swachh Survekshan, Bhopal ranked second among cities with a population of over one million.

According to the district’s environmental plan, 464,409 households within the Bhopal Municipal Corporation limits generate approx 882 tonnes of solid waste every day. This figure is expected to rise to 972 tonnes by 2030. Waste is collected using 719 vehicles. However, to manage this waste, the corporation has only 15 transfer stations and six material recovery facilities.

According to the municipal corporation’s own data, daily around 64 tonnes of solid waste is not collected. Official documents cite unauthorised colonies and settlements as the reason. However, the same documents also state that the corporation does not have sufficient vehicles (trolleys) for collection.

Environmental activist Nitin Saxena had filed a petition before the National Green Tribunal (NGT) regarding illegal dumping of solid waste in various parts of Bhopal, especially near green belts and water bodies. On January 27, 2026, the NGT directed all urban local bodies in Madhya Pradesh, including Bhopal, to strictly comply with the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016.

What are the gaps?

Municipal vehicles are designed to collect six different types of waste separately, in practice, they only segregate wet waste, dry waste, and recyclable scrap such as plastic and metal. Explaining this, a sanitation worker from the municipal corporation said:

“Most people only separate wet and dry waste, and some do not even do that. The volume of wet and dry waste is so large that even after dividing the vehicle into two sections, the vehicle has to make two trips to collect waste from a single colony.”

Household waste is taken to transfer stations for segregation. In 2024, Saxena filed an RTI to know the amount of leachate is generated at these stations. Even after more than a year and multiple appeals, he has not received a response. According to Saxena, leachate from transfer stations flows into nearby water bodies. He argues that knowing the quantity of leachate and planning its treatment is essential.

In its recent order, the NGT has directed all urban local bodies in the state, including Bhopal, to establish an “Environmental Cell.” This cell must include an officer with relevant environmental qualifications, who can train staff involved in solid waste management.

According to the 2025 environmental plan, the municipal corporation signed an agreement with NTPC to set up a 400-tonne-per-day torrefied charcoal plant using dry municipal solid waste. The NGT has asked for a compliance report on this project.

The question of monitoring

The new rules also introduce provisions related to bulk waste generators.

Central and state government offices, local bodies, public sector undertakings, commercial establishments, and residential societies can be identified as bulk waste generators if they meet certain criteria: a floor area of 20,000 square metres or more, daily water consumption of 40,000 litres or more, or daily solid waste generation of 100 kg or more.

Under the new rules, bulk waste generators themselves will be responsible for the environmentally sound collection, transport, and processing of the waste they generate. This is expected to significantly reduce the burden on urban local bodies and promote decentralised waste management.

Environmental activist Rasheed Noor Khan from Bhopal welcomes these provisions but raises concerns about monitoring. He asks how compliance by different entities will be ensured when even the municipal corporation’s existing waste management practices are not adequately monitored.

Saxena also points out that municipal officials often hold multiple charges and that there is no dedicated officer for the Swachh Bharat Mission within the corporation. As a result, sanitation is not prioritised. He also advocates for appointing technically qualified scientists as regional officers in the Pollution Control Board.

Overall, Bhopal still needs to do much more to be ready for the new rules. Segregating waste into four categories instead of two is a positive step, but it must be ensured that collection vehicles also maintain this segregation. Dumping of waste in green belts and near water bodies must be strictly curbed, and a dedicated officer must be appointed to monitor compliance with the new rules.

Support us to sustain independent environmental journalism in India.

Keep Reading

Story of Mala Nimbalkar: Rag Picker to Manager of MRF centre in Bhopal

In Bhopal’s Idgah Hills, Who is Segregating Our Plastic Waste?