Since January 2022, Madhya Pradesh has faced extreme weather on 598 days nearly one in every three days, a new analysis shows. In that time, 1,439 people have died from lightning, floods, heatwaves and storms. Crops on at least 82,170 hectares have been ruined, though the real loss is much higher. Over 20,000 homes were damaged or destroyed, and close to 6,000 livestock perished.

The figures come from four annual climate reports by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) and Down To Earth magazine. Groundreport.in studied the data from 2022 to 2025 to reveal how relentless weather is pushing India’s central state into a deepening crisis.

The data reveals a state where extreme weather has become the default condition rather than the exception.The central Indian state recorded 140 dangerous days in 2022, then 138 in 2023, then 176 in 2024, then 144 in the first nine months of 2025 alone. Nearly every other day now brings floods, lightning, storms or heat.

Death Toll Tells Real Story

But frequency tells only part of the story. The death toll shows the real shift. Madhya Pradesh recorded 301 deaths in 2022, dropped to 253 in 2023, jumped to 353 in 2024, then surged to 532 in just nine months of 2025. The state now leads India in climate fatalities, surpassing all other regions.

This year closed out September with a grim distinction. The 532 deaths through September made Madhya Pradesh the deadliest state for extreme weather in India. Floods drowned 348 people. Lightning killed 183. Heat claimed one life. The toll comes from the 2025 report tracking conditions from January through September, which found dangerous weather on 270 of 273 days nationwide. Madhya Pradesh faced threats on 144 of those days.

The four-year analysis reveals patterns of escalating violence in weather events, collapsing seasonal boundaries, and government data so inconsistent it obscures the true scale of destruction. This is not a story about numbers climbing in neat progressions. It is about systems breaking under sustained assault. It is about a state where lightning strikes with grim regularity while floods triple their death toll, where winter brings rain instead of cold, and where farmers can no longer predict which season will bring which threat.

When Lightning Kills

Lightning has struck Madhya Pradesh on between 81 and 103 days every year since 2022. In 2022, lightning killed 164 people across 97 dangerous days. The next year brought 152 deaths over 81 days. In 2024, the count rose to 180 deaths across 103 days. Through September 2025, 183 people have died on 91 lightning days.

The victims follow a pattern. Most die in fields during sudden storms. Farming does not stop for darkening clouds. Workers caught on open ground run for shelter that does not exist. In some areas, the same lightning strikes that kill farmers also destroy livestock and storage structures, compounding immediate loss with long-term economic damage.

The consistency of lightning deaths across four years stands in stark contrast to everything else. While floods and storms have grown more chaotic and deadly, lightning maintains its grim regularity, roughly 160 to 180 deaths annually regardless of other weather patterns. This baseline of death has become background noise in a state facing far worse escalations elsewhere.

Flood Surge That Changed Everything

Heavy rain and floods killed 112 people in 2022 across 85 dangerous days. The next year saw 95 deaths over 82 days. In 2024, deaths jumped to 160 across 89 days. Through September 2025, floods have killed 348 people on just 88 days.

The frequency barely changed. The impact more than tripled.

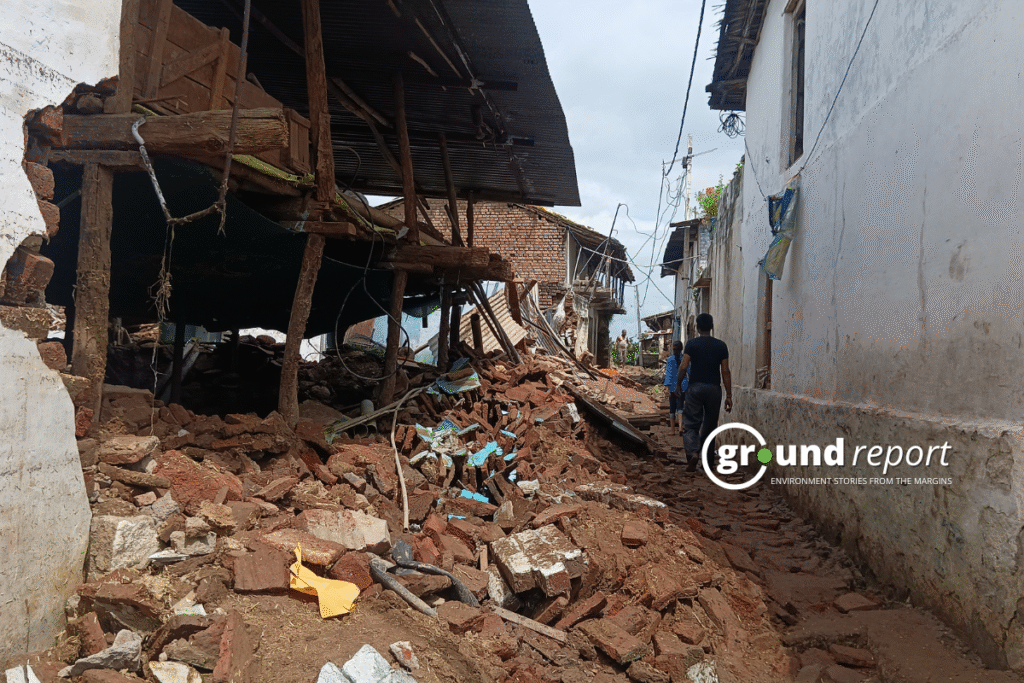

Farmers describe what changed: rain now falls in concentrated, violent bursts instead of steady monsoon patterns. A single afternoon downpour converts fields to standing water deep enough to drown livestock. Mud houses collapse when walls become saturated within hours. Small streams that families waded across for generations now transform into fast-moving torrents.

The monsoon arrived in different forms between June and September this year. Madhya Pradesh faced extreme weather every single day during those 122 days. Heavy rain and floods occurred daily. Lightning and storms struck 104 times. Cloudbursts hit 17 times. The relentless pace gave communities no recovery time between disasters.

Families living near riverbanks now evacuate multiple times each monsoon season. In many villages, floodwater returns before people finish rebuilding from the previous episode. July brought rainfall 21.9 percent above normal this year. September surged 43.7 percent above average. These surpluses sound manageable in percentage terms. On the ground, they mean walls of water moving through populated areas with deadly force.

The Heatwave Puzzle

Heatwave data presents contradictions. Madhya Pradesh saw heatwaves on 38 days in 2022 with zero recorded deaths. The next year brought only 12 heatwave days but 4 deaths. In 2024, heatwaves lasted 28 days and killed 13 people. Through September 2025, 13 heatwave days have produced one death.

Temperature records reveal what raw heatwave counts conceal. February 2025 became India’s warmest February in 124 years of record-keeping, according to the India Meteorological Department. The national mean temperature hit 22.04 degrees Celsius, 1.34 degrees above normal. Central India, which includes Madhya Pradesh, recorded temperatures 1.88 degrees Celsius above normal.

March continued the pattern with central India logging its eighth-highest mean temperature at 28.04 degrees Celsius. Then May delivered a jarring reversal, Madhya Pradesh recorded its second-lowest maximum temperature for May in more than a century, falling 2.63 degrees below normal.

These wild swings make planning impossible. Farmers cannot predict when to plant heat-sensitive crops. Construction workers do not know which months will be safe for outdoor labour. Health systems cannot prepare for heat stress when temperatures fluctuate so dramatically.

The data puzzle has another layer. The IMD now compares current temperatures to the 1991-2020 baseline period instead of the earlier 1961-1990 reference. This warmer baseline can make some heatwaves appear less severe in official classifications even when people experience dangerous conditions.

When Winter Started Flooding Fields

The 2025 report documents something unprecedented in central India’s climate history: winter brought heavy rain.

January and February have delivered dry, cool weather for as long as meteorological records exist. Farmers plant winter crops knowing these months will stay moisture-free. This year broke that pattern. Across India, January and February saw 51 days of heavy rain, floods and landslides. Farmers in Madhya Pradesh reported winter crops damaged by moisture at critical growth stages. Stored grain became wet. Families faced repairs before the monsoon arrived, meaning two rounds of expensive damage in one year.

The pre-monsoon season has also transformed. March and April used to bring hailstorms as the primary danger. Now heavy rain and floods appear during these transition months with increasing frequency.

March 2023 brought unprecedented pre-monsoon violence. Storms killed 42 people in Madhya Pradesh. Hailstorms tore through wheat fields days before harvest, shredding roofs across multiple districts. Farmers rebuilt walls and storage sheds, then watched them get damaged again weeks later.

The breakdown of seasonal boundaries means farmers can no longer rely on traditional calendars. When to sow, when to harvest, when to store grain, these have become gambles instead of calculated choices based on generations of experience.

Vanishing Cold

Cold waves have nearly vanished from Madhya Pradesh’s climate record. The state saw 21 cold-wave days in 2022 that killed 25 people. The next year brought 6 cold days and 2 deaths. In 2024, cold waves appeared on 8 days with no deaths. Through September 2025, just 5 cold-wave days with no fatalities.

Winters are shorter. Nights stay warmer. The chill that once defined December through February has retreated. For agriculture, this means pests that used to die off in winter now survive year-round. For health, it means diseases that cold used to suppress can circulate longer.

The divergence between event frequency and death counts marks the most alarming shift. The state experienced its highest number of dangerous days in 2024 (176 days) but its highest death toll in 2025 (532 deaths through September). Individual events are hitting harder than before.

May and August 2025 saw extreme weather on all 31 days. The state recorded dangerous conditions during eight consecutive months from February through September.

Numbers That Don’t Add Up

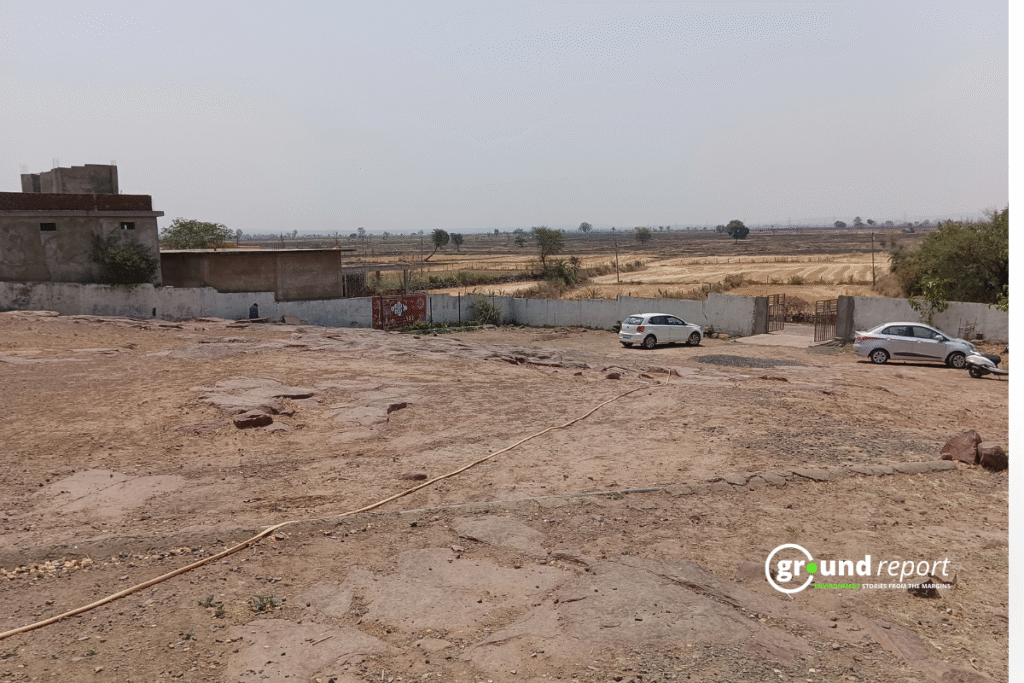

Official crop damage data defies credibility. Government reports show Madhya Pradesh reported zero hectares of damaged crops in 2022 despite facing 140 extreme weather days. Media reports at the time documented large areas ruined during the monsoon. For a major farming state under that level of climate stress, a zero-loss entry is not believable.

The pattern repeated in 2023. Madhya Pradesh again reported no official crop damage despite 138 extreme weather days. CSE, quoting media reports, documented at least 45,000 hectares of crops destroyed by hail, floods and sudden rain.

In 2024, reported damage was 25,170 hectares. Yet the CSE report noted that the Centre did not quantify monsoon losses for Madhya Pradesh, even as district-level reports described widespread destruction. Through September 2025, official figures show just 12,000 hectares damaged, while central India as a region recorded 8.42 million hectares of crop loss, the highest in the country.

These swings do not reflect real changes on the ground. They show a recording system that keeps shifting. The reports themselves admit that crop loss data for Madhya Pradesh remains incomplete, especially during monsoon months when most fields are hit.

Livestock losses show the same pattern. CSE records listed 3,592 animal deaths in 2022. In 2024, the number fell to 61, impossible for a state with 176 extreme weather days. This year already shows 1,799. The drop to 61 points to a collapse in reporting, not a sudden decrease in losses.

Home damage numbers move with similar confusion: 6,646 damaged structures in 2022, 2,626 in 2023, 7,278 in 2024, 4,089 in 2025. Every monsoon becomes a fight to keep houses standing. This cycle drains money that could go toward better livelihoods.

What the State Cannot See

The four reports treat Madhya Pradesh as a single unit. This aggregation hides critical internal variation. Some districts flood repeatedly while others face long dry spells punctuated by sudden storms. Villages near rivers contend with overflow while cities struggle with clogged drainage.

Without district-level data, designing targeted protection becomes nearly impossible. Which communities face the greatest flood risk? Which areas see the most lightning? Where do hailstorms concentrate? State-level data cannot answer these questions.

Warning systems fail to reach rural areas in time. Many people depend on mobile phones for alerts, but networks collapse during storms. In remote locations, warnings arrive only after damage begins. Even when warnings function, many villages lack safe shelter options.

Madhya Pradesh’s crisis reflects wider regional breakdown. Central India recorded 1,093 deaths from extreme weather between January and September 2025. The region experienced dangerous conditions on 200 of 273 days. Crop damage reached 8.42 million hectares.

Sunita Narain, director general of CSE, addressed the scale at the report launch: “The country no longer needs to count just disasters. It must understand the scale of response required. These events will continue, and we need both global cooperation and strong domestic action.”

Climate models project extreme weather will grow more frequent and severe. The data from Madhya Pradesh confirms this trend is already underway.

Not a Temporary Spike

The analysis reveals a state not just experiencing more extreme weather but worse extreme weather. Deaths climbed from 301 to 253 to 353 to 532 across four years. Event days fluctuated without clear trends: 140, then 138, then 176, then 144.

The divergence between frequency and severity marks the critical shift. Individual storms, floods and heat episodes now carry far more deadly force than before.

Madhya Pradesh needs infrastructure that can withstand sustained climate assault. Rural areas need warning systems that function when networks fail. Towns need drainage that handles sudden massive rainfall. Riverbanks need barriers that protect adjacent villages. Homes need construction standards that resist flood damage. Farmers need crop insurance that pays out based on accurate damage assessments.

All of this requires transparent data collection and honest reporting about what is being destroyed and where.

The four reports reveal a state under mounting pressure, escalation from chronic stress to acute crisis. This is not a temporary spike. It represents a fundamental shift in what normal weather means for Madhya Pradesh.

The state will face more years shaped by floods, storms and collapsing seasonal patterns. The question is whether it can build protective systems fast enough to prevent death tolls from climbing even higher.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

He Left the City to Farm, But Tigers Made the Fields His Biggest Risk

Sheopur’s farmers: Bad weather, crop failure & financial hardship