Kashif Farooq Bhat was 14 when he first saw a hangul. It was nothing like the majestic stags of his grandfather’s tales, powerful creatures with sprawling antlers, gliding through the valleys of Dachigam National Park near Srinagar, Kashmir. Instead, the animal lay dead on a riverbank, killed by a leopard that had abandoned the carcass.

“I had imagined the hangul to be small, like a goat. But when I stood before it, I saw how wrong I was. Even dead, it was glorious. Those antlers… were really something!”

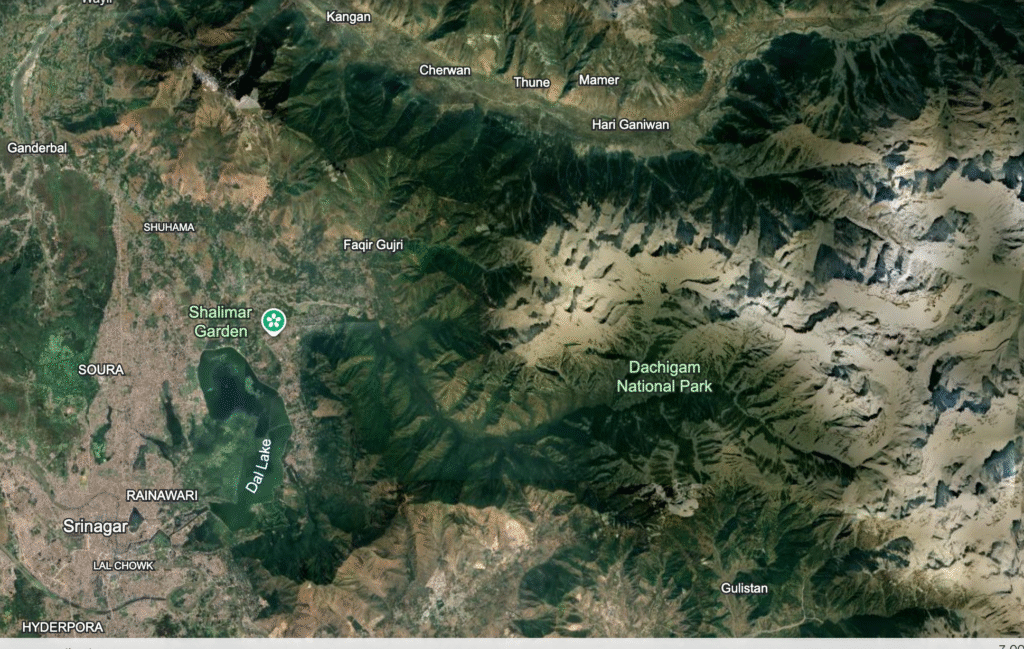

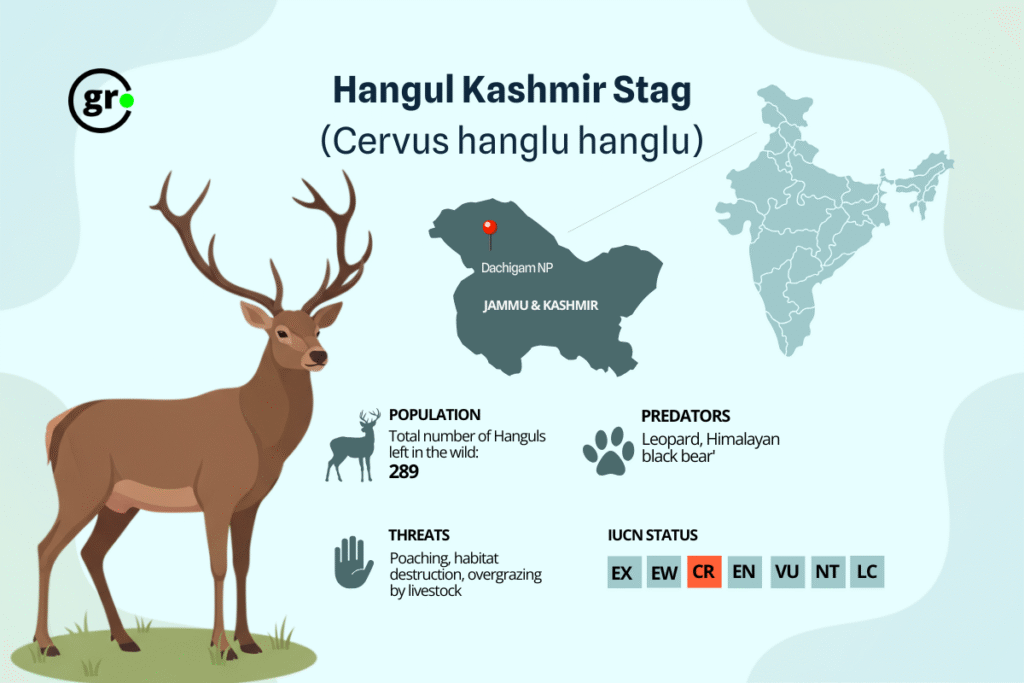

The Hangul, also known as the Kashmir Stag (Cervus hanglu hanglu), is a critically endangered species of the red deer that lives only in the Kashmir Valley and is the state animal of Jammu and Kashmir. Most of the remaining deer can be found in Dachigam National Park near Srinagar, with a few smaller groups scattered around nearby forest areas.

The national park, once the private hunting preserve of the Maharaja of Kashmir, was established in 1910. It became a wildlife sanctuary in 1951 and was declared a national park in 1981.

Kashif’s great-grandfather once guarded these forests; his grandfather and father, Farooq Ahmad, followed suit. Kashif, now 24 years old, walks the same trails. Back in the day, his grandfather saw herds of 40 or 50 hangul; now Kashif counts only a scattered few.

“You can walk for hours without spotting one,” he said, brushing the mud off his boots near Dachigam’s southern ridge. “They’ve retreated so deep, it feels like they’re fading into memory.”

The species is listed as ’Critically Endangered‘ by IUCN and is listed under Schedule I of the Indian Wildlife Protection Act, which grants it the highest level of protection and prohibits all hunting and trade.

For decades, the hangul have faced relentless hunting, pushing them to the brink of extinction. Although conservation efforts have slowly begun to revive this magnificent species, the increasing numbers don’t tell the whole story.

The hanguls continue to battle shrinking habitats, the threat of inbreeding, human encroachment, and the growing impact of climate change.

When the Hangul Roamed Free

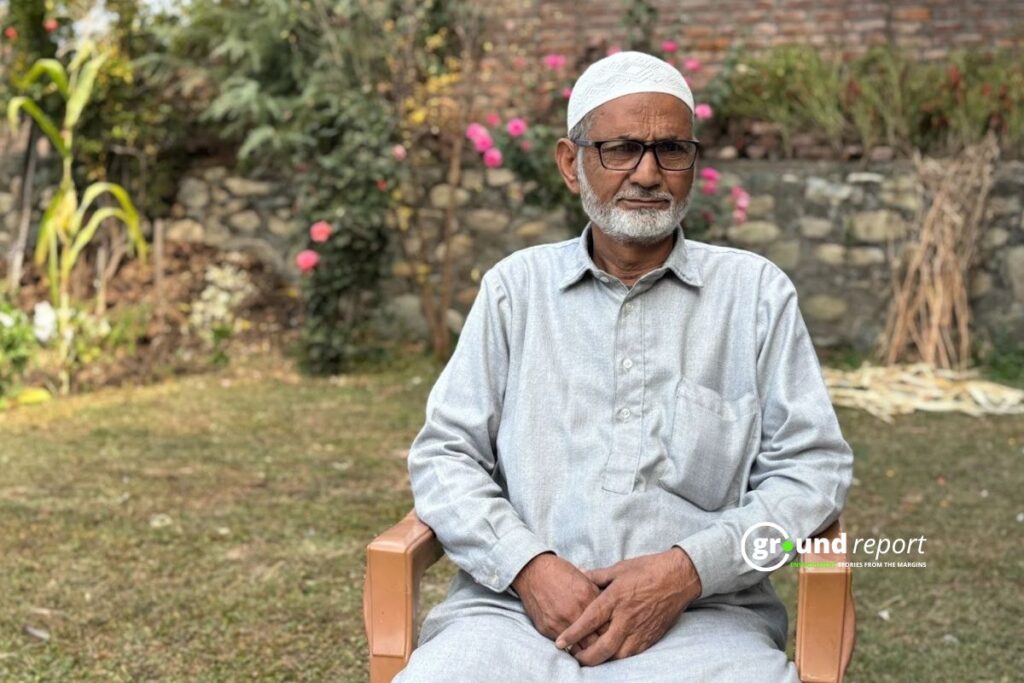

One kilometre from Dachigam, in the village of Muftibagh Harwan, Ghulam Ahmad Bhat, 68, sits in his courtyard.

“My father, Ghulam Mohiuddin, worked as a wildlife guard when I was 10 or 12,” he says.

As a child, Bhat would walk to Dachigam carrying lunch and dinner for his father. During harsh winters, a hangul would come to the edge of the guard quarters, looking for the willow branches his father and three other guards would keep out as food.

“My father, Ghulam Mohiuddin, worked as a wildlife guard when I was 10 or 12,” he says.

As a child, Bhat would walk to Dachigam carrying lunch and dinner for his father. During harsh winters, a hangul would come to the edge of the guard quarters, looking for the willow branches his father and three other guards would keep out as food.

“It was beautiful,” Bhat remembers. “You cannot imagine how a person feels when they see it.”

In the early 1900s, between 4,000 and 5,000 hangul roamed the Kashmir region. The hangul once ranged across a much bigger area. They went 200 kilometres north to Gurez Valley and 400 kilometres south to Kishtwar.

By 1940, heavy hunting had reduced them to merely 130 or 140. They stood at the edge of extinction. In 2008, only 127 hangul were counted, the lowest ever recorded.

Since the 1970s, the wildlife department set up anti-poaching patrols, protected habitat, and ran awareness programmes in local communities.

The population increased from 127 in 2008 to 323 in 2025, said Minister of Forest, Ecology and Environment, Jammu and Kashmir, Javed Ahmed Rana on July 9, 2025. But the official report has not been made public yet.

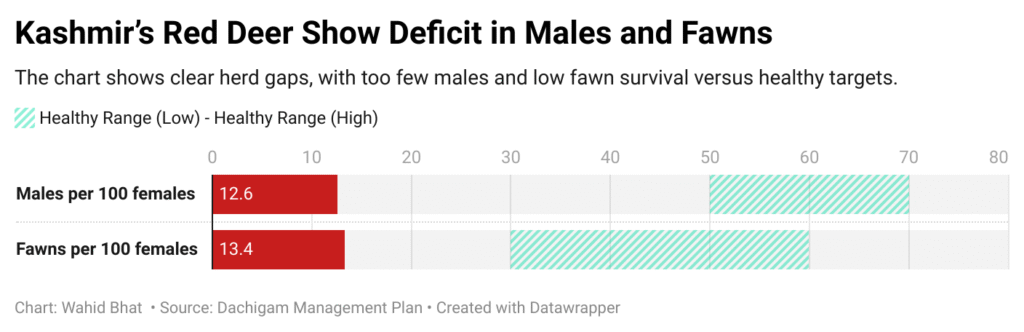

Amid the slowly growing numbers, the demographics reveal another problem. The management plan shows that in 2021, there were only 12.6 males for 100 females and just 13.4 fawns for 100 females.

A healthy population usually has 50 to 70 males and 30 to 60 fawns per 100 females. These skewed ratios reveal high male deaths and low fawn survival.

Many models give the hangul a 25% chance of dying out completely within 100 years. Worse: if poachers kill just a few more each year, or if winter deaths rise by 5%, that extinction risk jumps to 90%. “There is a dire need for urgent measures,” the management plan warns.

Concerns Genetic

Apart from this, the skewed sex and age ratios show deeper genetic and ecological stress.

“There is little or no gene flow in the population,” reveals Dr. Khursheed Ahmad, a senior scientist and Head of Wildlife Sciences at Srinagar’s Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology (SKUAST). He has studied this impact for years.

“The hangul groups are breeding within themselves, which leads to inbreeding depression. This weakens the population and affects both survival and reproduction,” he added.

The management plan page 52 shows the deer have “relatively low genetic diversity compared to other red deer species.” Their genes are becoming too similar, like copies of copies losing detail with each generation.

In a strong population, animals carry many different versions of genes, which helps them fight disease and adapt to change. When that diversity drops, as it has with the hangul, the population becomes genetically uniform. This makes the species more vulnerable to illness, climate stress, and sudden environmental shifts.

Though a 2023 genetic study found healthy genes, no inbreeding, and no recent genetic crash.

The captive breeding programme at Shikargah Conservation Reserve is still in its early stages. It currently houses four female hangul, but no male. “We are still trying to trap a male,” says Dr Mohsin Ali Gazi, Veterinary Officer with the Department of Wildlife Protection. “Only then can proper breeding begin.”

A Landscape that Changed

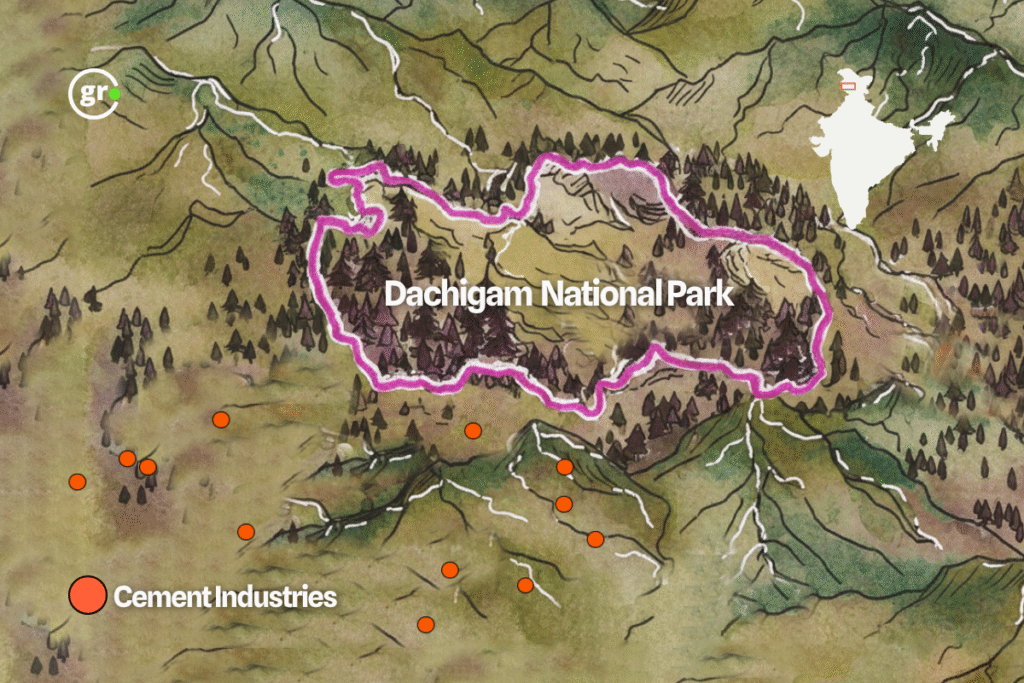

“The construction of cement factories has limited the area of the hangul,” Khursheed Ahmad says in the Mongabay-India documentary. “They are now mostly restricted to the Dachigam National Park.”

The hangul, highly sensitive to sound and smell, avoids such disturbed zones. Various reports show that noise and dust from industries or mining activities near protected areas reduce the space available for wildlife.

The six or seven cement factories near Khrew are very close to the national park.

The Forest, Ecology and Environment Department, in a written reply to a question from MLA Hasnain Masoodi in J&K Legislative Assembly on November 1, 2025, said the cement factories in the Khrew–Wuyan belt are “complying” with pollution control norms after inspections and multiple notices from the J&K Pollution Control Committee.

“Cement factories in Khrew and Khonmoh operate outside the limits of the Dachigam National Park and its Eco-sensitive Zone, which is considered a viable habitat of the Kashmir stag (hangul),” the Minister said in the statement.

During our visit to Dachigam, the presence of security forces was heavy. Multiple checkpoints dotted the roads. In Kashmir, security is necessary, but it adds another layer of disturbance to an already stressed ecosystem.

A study by the Wildlife Institute of India published in the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society looked at this closely.

The research team found that the hangul now occupies just 504 square kilometres in the Kashmir Valley. Of this, only 148 square kilometres provide actual habitat, 84 in Dachigam, 52 in the surrounding areas, and 13 in the southern areas.

The Dachigam Management Plan 2020-2030 published in 2020, prepared by the Department of Wildlife Protection, led by Wildlife Warden Altaf Hussian, with guidance from the Chief Wildlife Warden. It focuses on Hangul conservation, habitat care, fire management, research, and human-wildlife conflict.

The plan states “excessive grazing by nomadic tribal livestock in alpine pastures” as “a major limiting factor.” Each year, Gujjar-Bakarwal pastoralists migrate through the hangul’s summer habitat with thousands of sheep, goats, and cattle. Apart from that, there are fences marking boundaries, roads cutting through the forest, and construction noise from nearby villages.

“The hangul is often stuck in only 20 to 30 square kilometres in the middle of Dachigam,” explains Advocate Nadeem Qadri, who has been fighting for the hangul since 2000. “It avoids the upper parts because of grazing pressure and the lower parts because of human infrastructure.”

“In summer, we run anti-grazing camps,” explains Shabir Hussain, a naturalist with the Wildlife Department who has spent over 15 years in the Dachigam National Park. “We try to stop the livestock from entering the hangul habitat. Employees stay at entry points 24/7 to save the grazing areas.”

Advocate Nadeem Qadri has been fighting for the hangul since the year 2000.

Sick Animals in a Stressed Habitat

The livestock brings more than just grass competition. The Management Plan page 49 shows a 32.26% parasitic infection rate in the hangul during summer. It says this is “potentially influenced by cross-species parasitic infection from livestock.”

The Management Plan page 93 documents past disease outbreaks: John’s disease in 1978, Foot-and-mouth disease in the 1930s, suspected cases of anthrax, tuberculosis, and brucellosis.

“The hangul is a very sensitive animal,” Dr. Mohsin Ali Gazi said during our visit to Dachigam’s wildlife healthcare centre.

His team collects faecal samples, hair, and skin scraps to check for parasites and nutritional problems. “We look for worm infestations, parasite infestations. If we find them, we plan a deworming treatment.”

Parasite loads go up when animals face stress, poor nutrition, or contact with domestic livestock. “A stressed habitat makes animals sick,” he says.

The Struggle of Winter

“In summer, we prevent livestock entry. In winter, we provide supplementary food”, Shabir Hussain said.

The department stockpiles willow branches, locals call them bachas, and vegetables. When snow covers natural food sources, the staff place these supplies where the hangul can reach them easily. And, this is suggested to copy natural feeding patterns to avoid “microhabitat degradation”.

“Sometimes release of funds happens at year’s end. This creates great difficulty in achieving annual targets,” the management plan read.

Climate Change Impact

Climate Change presents its unique challenge in the valleys of Kashmir. Ghulam Ahmad Bhat shares, “In my childhood, snow would fall continuously from December until March. So much snow that it reached the height of small children. That’s why the hangul would come down; they wouldn’t find anything to eat up there.”

Today, snowfall is lighter and the winters end earlier, so the hangul no longer moves the way they once did.

This shift disrupts their natural rhythm. The hangul have always followed the seasons, living between 1,600 and 2,400 metres above sea level in winter and moving above 4,000 metres in summer. For thousands of years, this cycle guided their lives.

Now, with their movement disrupted, and their habitat reduced, they spend more time in vulnerable zones where predators live.

The management plan confirms that hangul remains appear in 25% of leopard droppings. But other studies suggest that the hangul makes up a much larger share of the leopard’s diet.

A Question of Survival

Building on years of fieldwork and legal battles, conservationists have begun shaping a long-term recovery roadmap, Project Hangul 2035.

With a partnership with Cambridge University, the 15-year project sets an ambitious goal: to grow the population beyond 500 individuals by 2035 and bring the entire landscape under a single Conservation Management Authority.

“I don’t want a situation tomorrow where our children and grandchildren know these species only through photographs in books, like the dodo or woolly mammoth. That would be a tragedy we must not allow,” Chief Minister Omar Abdullah said at the 2nd International Conference on the Hangul in September 2025.

“Protecting the hangul is protecting Kashmir’s ecological soul,” Qadri says firmly. His biggest win came through the High Court in 2017, when he got orders that marked out over 2,000 square kilometres of protected areas. This included Dachigam, Overa-Aru, and Tral Wildlife Sanctuary.

Project Hangul 2035 tries to reopen the old route between Dachigam and Tral by restoring the corridor through Khrew and Khonmoh. These areas once connected the two habitats, but disturbance and grazing cut that link.

There is a clear intent. And, then there are individuals, like Kashif on-ground implementing these plans or holding the authorities accountable.

Dusk falls over Dachigam, and he stands on a ridge, watching the forest turn dark. Somewhere below, more than 300 hangul move through what is left of their home. His great-grandfather once guarded these forests when thousands of hangul lived here. Now only a few hundred remain.

The hangul will not survive on numbers alone. It needs open corridors, protected grazing zones, and stronger care of disturbed forest areas. It needs steady funding, clear rules, and real checks on nearby industries. The work must move faster, and with science and these steps, the hangul can recover.

As night grows quiet, Kashif hears a faint call from the valley. Maybe a hangul. Perhaps just the wind. He will return tomorrow at dawn, hoping to see antlers rise from the mist.

This story is part of the IUCN’s Stories of Hope Media Fellowship, under the Himalaya for the Future initiative.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Small Wild Cats in Big Trouble: India’s First National Report Released

After Tragedy, Families Face Delays in Tiger Attack Compensation

Stay connected with Ground Report for underreported environmental stories.