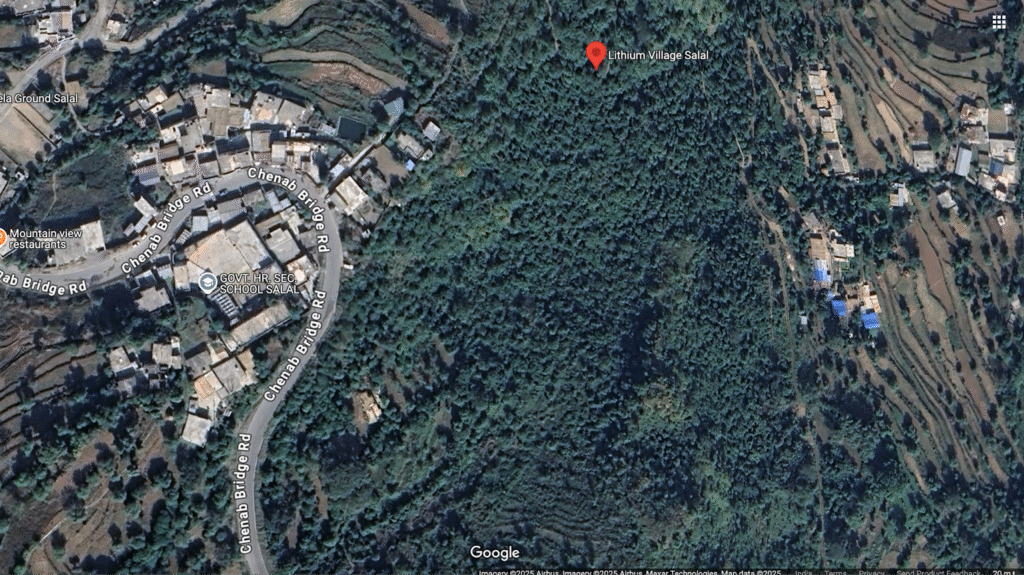

Mila Kumari toils on her rocky agricultural land. Her struggles to grow crops are compounded by water scarcity. She says, “farming here is not easy… the soil is rocky and we struggle for water every day. We don’t even have proper markets to sell our crops.” She has lived in the Salal village for 38 years. She was born, and brought-up a few minutes away from where she lives now after marriage. The tale which can be repeated for several other women in the village, possibly even for some men. Lately, her village has conjured a new identity. Now, it is easier to find Salal as a lithium village on Google Maps, after the Government of India’s announcement of lithium reserve discovery. Almost overshadowing the village’s pre-existing realities.

This white-shinny metal–lithium– is crucial for India’s energy transition, as it is used in building batteries for energy storage. But, now the villagers fear that the lithium mining will take away their land and livelihoods.

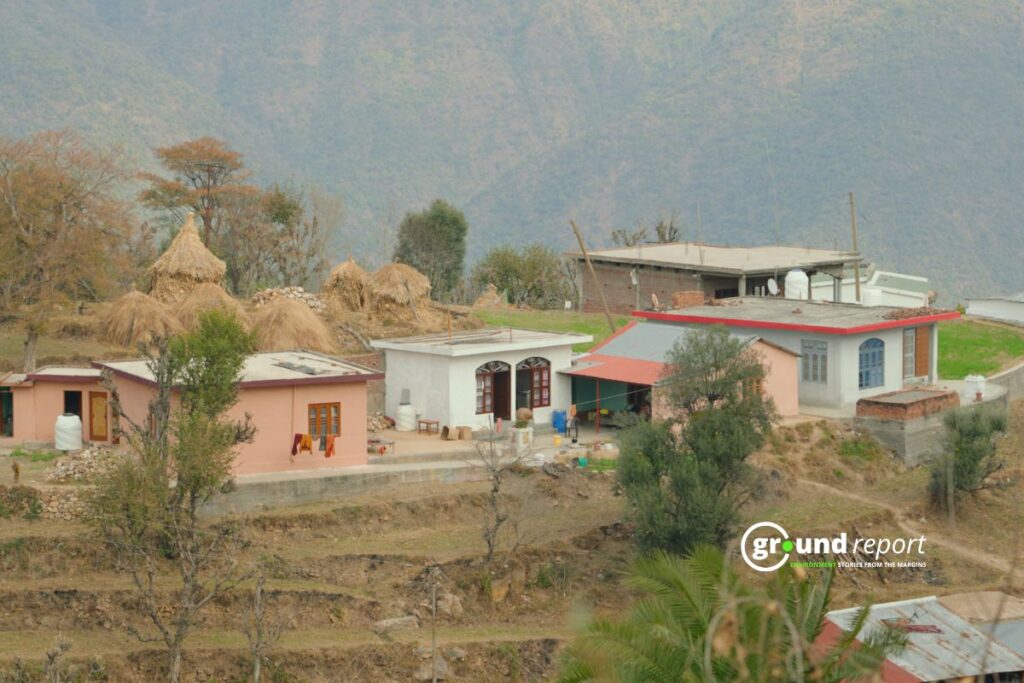

Salal village of Reasi, an underdeveloped district of Jammu and Kashmir, is uniquely beautiful. The Chenab river flows from all four sides, and mountains appear closer than ever. It is serene. Mila’s family belongs to the Chamar community, and owns five acres of land. They primarily grow maize and vegetables, with occasional crops of mustard and wheat, through rainfed agriculture. Most of their produce is for their own consumption, though they do sell a small portion. For generations, Mila’s family has worked in these fields. Most of the work is still done manually, which makes farming more labour-intensive and hard to earn a steady income. Mila says. “Last year, they harvested 3 quintals of maize and sold half of it in Reasi at ₹3000 rupees per quintal”.

Mining promises, water worries rise

While we speak with Mila Kumari, her daughter, Mitinia Kumari, returns from the market. Quite like her mother, she has lived all her 16 years in this village. Evidently, for her, Salal isn’t just a place, it is home. “I’ve spent my whole childhood here, playing and growing up… I want to stay with my family and friends. I can’t imagine living anywhere else,” she adds. But, she would have to leave this village, because she wants to be a doctor, and there are no colleges here. The village is home to nearly 3198 people as per 2011 census, but there are no educational institutes or proper medical facilities. Though one Ayushman Bharat centre, and a pharmacy exists. For serious medical needs, villagers must travel to Reasi district, an expensive and time-consuming journey through mountainous terrain. Even without the threat of mining, life in Salal is difficult.

260 kms away from Mila’s Kumari’s home is Kashmir University, in the capital city of Srinagar. Here, Dr Sarah Qazi serves as hydrogeologist and the only female faculty member at the Department of Earth Sciences. Dr Qazi was busy with her research, when she first heard the news of lithium discovery. In the cold winters of February, 2023, she remembers to be engulfed in the dual feeling of happiness, and concern. She understands the environmental concerns related to the mining sector as a whole. She said, “If done in a balanced way, it will be useful. But if we take out lithium without caring for the environment, it will create problems. Saying no to lithium is not the solution. The focus should be on doing it in the right way.”

Dr Qazi was born in Sopore, a town in North Kashmir close to Wular Lake. This innately made her curious about water bodies in the region. She said Kashmir’s water system is unique and not fully understood. “In Kashmir, most of our water comes from springs that form in limestone areas, called karst springs. These springs depend on underground water flow, but we don’t fully know how big these water paths are. Some springs have dried up completely,” she said.

The region has faced a steady decline in rainfall over the last five years, with 2024 being the driest in five decades, recording only 870.9 mm, a 29% shortfall from the normal annual average of 1232.3 mm. Now, the lithium discovery has brought new worries. Mining could harm the soil and water, making farming even harder. People fear lithium mining will take away the little water they have and ruin the land. Without irrigation, the reliance is on the increasingly unpredictable rainfall. Mila Kumari recalls how the village came together in 2021 to build the water storage structure shown in the image. “We started this to save rainwater because our streams were drying up. But now, even the rain has stopped… it is not like before,” she says with concern.

Extracting power, endangering fragile lives

According to a report published by Wired revealed in 2018, it takes about 500,000 gallons of water to extract one ton of lithium. Some reports even suggest that it takes around 2 million liters of water to extract one ton of lithium through evaporation. In this context, the question arises: if the government has not been able to provide water to the people for so many years, how will they arrange for water for mining? Dr Qazi warns that mining can pollute groundwater by releasing harmful metals like arsenic, lead, and mercury into groundwater. “These toxic elements don’t just affect water; they enter the food chain, harming plants, animals, and people,” she explains. Mining can also damage natural water sources, making it even harder for villagers to find clean water.

Lithium extraction is done primarily in two ways: from brine (salty water) or hard rock deposits, specifically spodumene. Brine extraction involves pumping salty water from underground or surface sources into large evaporation ponds. As the water evaporates, lithium remains behind, and further processing refines it into lithium carbonate or hydroxide. This method, mainly used in countries like Chile, is considered more efficient in terms of energy consumption. On the other hand, hard rock extraction, common in countries like Australia, involves digging up lithium-rich rock, crushing it, and processing it chemically to extract lithium. This process is more energy-intensive and involves higher levels of environmental degradation.

The process of extracting lithium from the Reasi deposits is further complicated by the presence of clay deposits mixed with other minerals like bauxite. This makes extraction more difficult and untested on a commercial scale. The methods of extraction for such unique deposits have not been proven anywhere globally, and this lack of established techniques could be a significant barrier to the feasibility of large-scale mining.

Professor Pankaj Srivastava, a geology expert at Jammu University, said, “No separate ore mineral of Lithium has been yet reported from Reasi, but the lithium enrichment in Reasi Bauxite is because of lithium presence in the crystal lattices of clay and other alumina hydroxide minerals. Hence, the exact quantity of lithium that can be extracted from the bauxite is yet to be established. But the techniques for extraction, beneficiation, of lithium from bauxite are available elsewhere”.

In summer, Mila and her 16-year-old daughter Mitinia, along with other women, walk long distances to fetch water. “As I carry big pots, I wonder how long we have to live like this. If we must relocate due to lithium mining, I don’t believe city life will become any simpler,” she says. Mila says that water has become a big problem since the construction of the Chenab Rail Bridge, which started back in 2003. “Most of us depend on streams for drinking water because we don’t have pipes in our homes. But now, those streams have dried up too. We either wait for water tankers or walk almost 2 kilometers to collect water,” she says.

Villagers wait, water never comes

“During the construction of the Chenab Rail Bridge, the debris was directly dumped into the Chenab River, leading to contamination and rendering water unusable for any activity,” explains Saraf Singh Nag, Reasi’s District Development Council chairman and former Kashmir Administrative Service (KAS) officer. As per the regulations of the Construction and Demolition Waste Management Rules, 2016, any engineering project must have a designated dumping site for debris disposal. His exasperation is evident, he said, “I have been saying this for years, and I continue to tell every media person the same thing.”

For Dr Qazi, the water problem is part of the bigger issue. “We are facing water shortages not only in Salal but all over Kashmir,” she said. “Even in winter, when we should have plenty of water, we are seeing shortages. This shows how serious the situation has become.” She also said climate change is not the only reason for the water crisis. She said, “climate change is real, but we cannot blame everything on it. We need to take action and use climate-friendly solutions.”

However, according to the Ministry of Jal Shakti, Department of Water Resources, as of January 2022, there are 298 active groundwater monitoring wells across 11 districts of Jammu and Kashmir, including Reasi. Though pipelines have been installed in every home, the water still doesn’t reach them. This is despite the government’s Jal Jeevan Mission, which aims to provide tap water to every household in the Reasi district, where 90% of the area is covered under the “Har Ghar Jal” (water to every home) scheme. Mila’s family and other villagers have asked officials for help many times. Even when a minister visited in 2021, nothing changed.

Even with these struggles, Mila does not want to leave her village. “We have learned to live with these problems… cities are not good for us—too much pollution, too many vehicles. Here, at least we have fresh air, our land, and our way of living,” she adds.

Culture weighs against climate solutions

Mining in the seismic zones is a real concern as Dr Soumya Dutta points out. He explains, “When mining starts, it goes deep underground. As soon as it reaches the water table, the groundwater from surrounding areas will start flowing into the mining site. This will cause water levels in the area to drop. If the water is pumped out and moved elsewhere, that’s a common practice, but the real danger is in seismic zones.” He is the co-convener of South Asian People’s Action on Climate Crisis (SAPACC). We have a precedent also. In Basel, Switzerland, drilling for geothermal power caused water from the surface to leak into a seismic zone, which led to a series of earthquakes. This is the risk, using explosives in an active seismic zone and allowing water to seep into deeper layers can be very dangerous and irresponsible.

What concerns Dr Datta isn’t the potential environmental harm, but how little is known to the public. The tenders are put into the market for auction, but not assessment has been done. “Obviously the government knows more,” he said.

Dr. Raja Muzaffar Bhat, an activist from Srinagar, explained that the mountains in Jammu and Kashmir are fragile, making the region especially vulnerable to environmental problems from mining. He said, “The mountains in places like Reasi, Ramban, Udhampur, Doda, and others have a lot of sand and soil, which makes them unstable… The river flows through very delicate areas, and I’m not sure it will survive the impact. Even if gold is found here, it’s not worth mining. Our lives are more important than any resources.”

Back in Salal, Mila and her daughter Mitinia sit outside their home. Their agricultural land is where the drilling continues. The samples are then sent to the lab for tests. The water for the sample drilling is supplied through the water tankers. The project is in the G3 stage i.e., the tests are done to understand the viability of extracting lithium from clay deposits. India doesn’t have the technology for this yet. The officials continue their tests on the land which Mila toils. She continues her everyday life, with bleak prospects. As Mitainia says in Pahari, “if we leave, will we ever come back? What will happen to our fields, our home, our memories?”

In the distance, the sound of drilling machines is getting louder, a sharp, buzzing and grinding noise that vibrates through the air. The pipes are being inserted to get rock samples. As the global demand for clean energy technologies rises, the demand for lithium will also increase. A World Bank report in 2020 predicts that the production of minerals like lithium, graphite, and cobalt may need to increase by nearly 500% by 2050 to meet the demand for clean energy technologies.

Mila’s future is being rewritten. Definitely, her future will alter significantly if the exploration moves forward. The fragile ecosystem of Salal would be too. ‘For the greater good of humanity’ is the phrase we often denote to such developmental projects. Against climate change, for the renewable future, for the batteries that power electric vehicles, and to stabilize the solar or wind-powered electricity infrastructure. All these outcomes legitimize mining, displacement, and uprooting someone from their culture. But, when we’re fighting against an existential threat like climate change, what value does culture hold? That’s the question we’d have to grapple with several times in the coming future. Maybe we would even have to make a choice between the two, culture or the solution.

Officials come to the village more often now, talking about progress and the future. But to Mila and the other villagers, progress should not mean losing their home. If the exploration continues, one day Mila Kumari will understand that her village, her land, her community, and she herself has sacrificed and contributed to the greater good. But, will someone ask her? Maybe not.

Read part one of the story here: Lithium discovery spotlights a quaint Jammu village

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Highway Halt Puts Kashmir’s Fruit Economy at Risk

MP brings back Bhavantar as farmers lose soybean harvests

Stay connected with Ground Report for underreported environmental stories.

Follow us onX, Instagram, and Facebook; share your thoughts at greport2018@gmail.com; subscribe to our weekly newsletter for deep dives from the margins; join our WhatsApp community for real-time updates; and catch our video reports on YouTube.

Your support amplifies voices too often overlooked, thank you for being part of the movement.