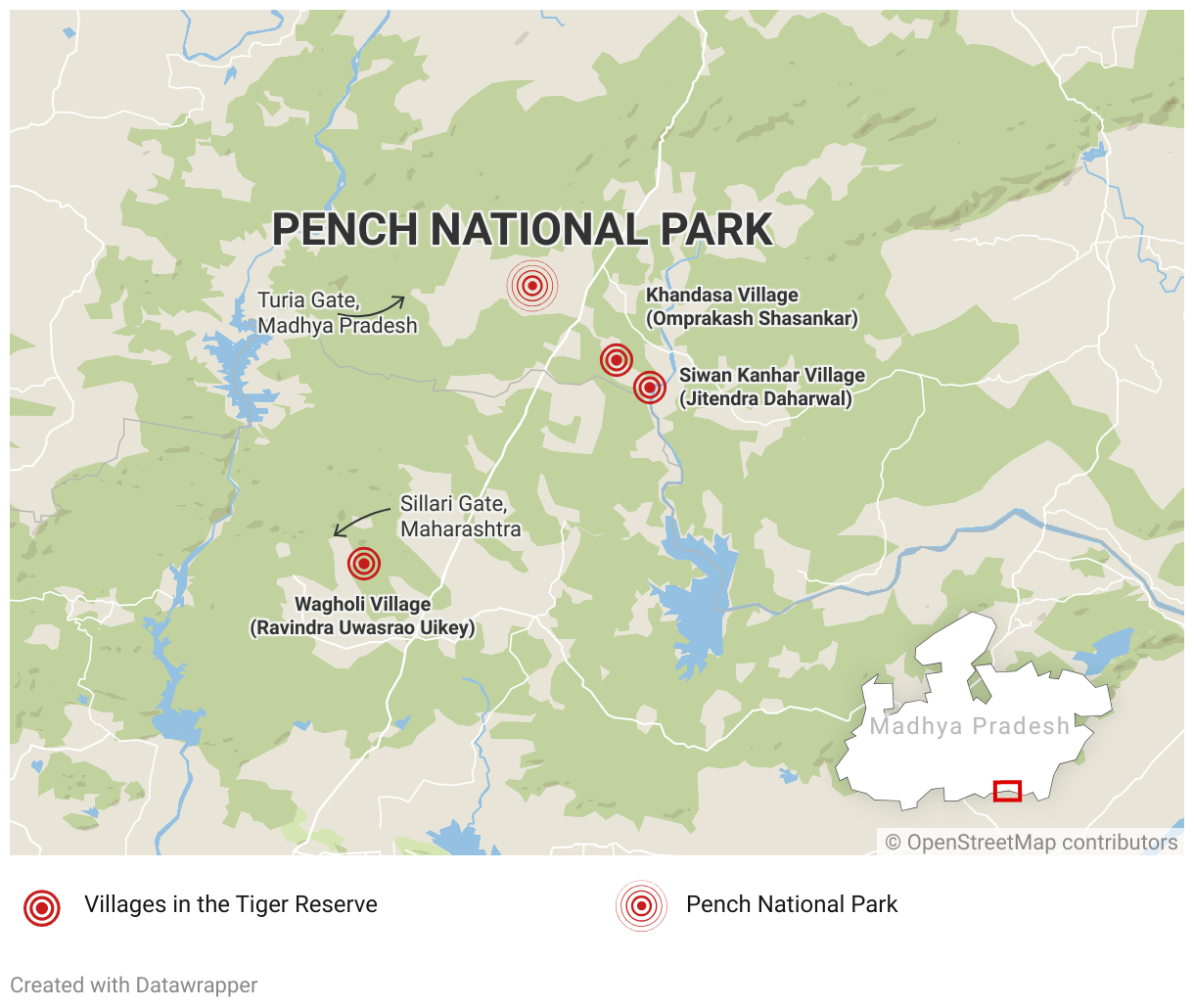

हिंदी में पढ़ें। In Wagholi village, Nagpur, 3.7 km from the Sillari Gate of the Pench Tiger Reserve, Ravindra Uwasrao Uikey fences his fields with a wire. This wire will soon be connected with a solar panel to ensure a continuous supply of 12 volts of direct current. He does this every year on his 13.07 acres of land. Within a week, his farm will be completely fenced after spending 700 to 800 rupees.

Uikey has used the solar fence since 2023. Before this, he would build a “manda” (machan) — an elevated hut-like bamboo structure built on wooden supports. He would spend nights sitting on the manda and vigil in the fields all night. The local people call this “jagli karna.” On one such vigil in December 2022, at 7 am, a tiger was eating a wild boar in Uikey’s field. His sister-in-law raised an alarm, and he found the tiger sitting just 150 meters away. After this incident, he stopped keeping vigil, and from 2023 onwards, he started using solar fences.

These incidents induce fear and impact labor hiring for the fields, particularly for the nighttime vigil. On the other hand, Jitendra Daharwal from Siwan Kanhar village, of Seoni district, Madhya Pradesh, had left his private job to take up farming. For these reasons, he wants to sell his 30 acres of land. Ground Report has published his story in detail here. Now, the solar fence protects Uikey’s entire field.

There are 125 tigers in Central India’s Pench Tiger Reserve, 77 tigers in MP, and 48 in Maharashtra. Though the protection isn’t necessarily from the tigers. The fences, in theory, prevent wild boar (Sus scrofa), chital (Axis axis), sambar (Rusa unicolor), and nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus) from entering his farm.

Omprakash Shasankar (69) has his 18-acre paddy crop in Khandasa village, near the Turia Gate of Pench Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh. On September 11, a small herd of wild boars (Sus scrofa) destroyed the maize crop planted in his home compound. Though in 2018, his Sugandhit Dhaan crop, a variety of Basmati rice planted on 3 acres, was eaten by wild boars overnight, just before the harvest.

He received 13,000 for his 30,000-rupee investment as compensation. Wild animals have regularly damaged his crops. “In the rabi season, I grow wheat. Spotted deer (Axis axis), sambar (Rusa unicolor), and nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus) destroy it,” he said.

Uikey had a similar experience when Randukkar(s) [local name for wild boar] ate his ready-to-harvest crop. “Spotted deer and nilgai eat the small plants just one and a quarter months after sowing,” he said.

For small farmers, the damage can be a large portion of their annual income. For instance, 55-year-old Gond farmer Shahdev Tekam farms only on one acre. In May this year, he had sown a moong (green gram) crop, putting in 10,000 rupees. But in June, Randukkar ate his entire crop. With an annual income of 60,000 to 70,000 rupees for him, this is a huge loss. He angrily said,

“You invest money and sow seeds, guard them day and night, and all the damage happens in five minutes– how would you feel? You think about it yourself… why should I tell you?

Between 2020 and 2024, Madhya Pradesh reported 406 human deaths, 5,804 injuries, and over 72,000 animal deaths from wildlife attacks, RTI data shows. Tiger attacks alone claimed 200 lives in Maharashtra between 2019 and 2023, but there’s still no central or state data on crop damage. But there are solutions with solar-powered fencing systems, solar deterrents, and even solar pumps to reduce these conflicts. And some farmers in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra are adopting them.

After repeated destruction, farmers get angry. There are local solutions like the Zatka (Shock) machine, not powered by solar. These have higher current running through them. But these fences not only harm animals but also kill humans. Manoj Pandre (35) and Ashok Bhalavi (36) installed electric fences in MP’s Pench. On July 24, they died from electrocution from the same electric fences.

According to a report released in October 2020 by Delhi-based NGO Wildlife Protection Society of India (WPSI), approx 1,300 wild animals died from electric shocks, whether intentional or accidental, between 2010 and 2020. This included 500 elephants, 220 flamingos, 150 leopards, and 46 tigers. According to this report, 74 wild animals were killed in Maharashtra, including 18 leopards and 16 tigers. In August this year, tiger ‘T-43’ in Madhya Pradesh’s Sanjay Tiger Reserve died after coming in contact with electric wires installed in a field.

That is why solar fences were distributed under Dr. Shyamaprasad Mukherjee Jan-Van Vikas Yojana, Mandal Pingle, Deputy Director of Satpuda Foundation, explained.

Solar Fencing to Protect Crops

The Maharashtra government launched the Dr. Shyamaprasad Mukherjee Jan-Van Vikas Yojana in July 2015. Under this scheme, farmers in villages adjacent to protected forest areas were given solar fences. The government bears 75% (Rs 15,000) of the cost while farmers contribute 25% (Rs 5,000). In March 2023, the state government announced it would spend 50 crore rupees to provide solar fences to 33,000 people under this scheme.

Uikey received his solar fence under this scheme, which included: a fence energizer with a direct current of 3 kV to 9 kV, and a 40-watt, 12-volt solar panel. It also comes with a 12-volt Sealed Maintenance Free (SMF) battery, 20 feet of connecting wire, and 10 kg of 1.5 mm GI (Galvanized Iron) wire.

In Maharashtra, more than 10,000 farmers have received solar fences under this scheme. In Madhya Pradesh’s Pench Tiger Reserve, Rajnish Singh, Deputy Director of Pench Tiger Reserve, tells us the department is doing the same here.

“Earlier, we started giving solar fences to Eco Development Committees with a 50% subsidy. We used to take Rs 7,500 from the committee and contribute the same amount from our fund to buy and give solar fences. Then we got support from a bank, now we give solar fences for just Rs 1,000. We deposit this money in the committee’s account directly.”

Singh says that Pench Tiger Reserve has provided fences to more than 1,500 farmers so far, covering almost 300 to 400 square kilometers.

While the forest department sees solar fences as a solution, Tekam’s experience might point towards the limitations. He received the solar fence two years ago. After animals ate up this moong crop, he fenced his fields. Though he says, “Wild buffalo (Bubalus arnee) break the fence. It’s not good for big animals.”

Like any machine, this fencing too requires maintenance. “It was observed that when weeds grow under the fence, it causes a short circuit, after which it stops working,” Pingle explained.

There are two policy-level issues with solar fences. Firstly, if a farm owner has been provided with a solar fence and a wild animal still causes damage to the crops, the owner will not receive compensation for the crop loss. Secondly, by the time people receive the solar fences, the Kharif (monsoon crop) season is already over. So, the delay in receiving solar fences is also a reason why people don’t adopt them.

From conversations on the ground, farmers widely see fencing as a solution to the menace of small wild animals. Though there are risks of short-circuiting and the need for re-wiring during the monsoon. The feedback can address the negative experiences and challenges.

Solar Deterrent Light as an Alternative?

Pingle points out another limitation: the solar fences obstruct the movement of wild animals. As a solution, his organization in Maharashtra distributed 500 units of solar deterrent lights to 450 farmers in the Pench Tiger Reserve and the Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve.

This is a square cone-shaped device with four LED lights. A lithium-ion battery stores energy produced through a small solar panel. This device, developed by Katidhan—a company focused on technical solutions to reduce human–wildlife conflict—is called Parabraksh, a Kannada word meaning “protection from wild animals.”

The device is tied to the pole. Once operational, it will flash a light and create random patterns for up to 250 meters. This gives the wild animals a false alarm of human settlement or presence. One light works effectively for one hectare. The company says that the light can protect from foxes, wolves, nilgai, wild boars, the big cat family, and even elephants.

Aditi Patil has been working in wildlife conservation for the past 10 years. In 2024, she started a company called ‘Conservation Indica’ to ‘elevate traditional ecological knowledge and democratize conservation research.’ She used Katidhan’s Parabraksh to reduce conflict between pastoral communities and leopards in Gujarat’s Surendranagar. Aditi and her team had mixed experiences with this device.

The local semi-nomadic communities create circular enclosures (called ‘vagda‘ in the local language) with thorny tree branches to keep their livestock. They installed four Parabraksh around two such vagdas where two male leopards used to frequent. At one vagda, the leopard reduced its visits, but at the other vagda, the leopard still hunted and took livestock.

Aditi, explaining the possible reason, says, “Where Deepu (the leopard) hunted, there was already a street light. It’s possible that since Deepu was already accustomed to that light, this light didn’t work on him.”

Pingle identified this issue early on. He said with certainty: the light’s location has to be changed regularly. Though the members of the big-cat family are quite sharp-minded predators, Aditi said, light alone won’t work on them. Perhaps, adding sound and motion to the device might have some effect, she suggests.

Human-wildlife conflict has several causes, one of which is agricultural fields being adjacent to forest areas. Solar fences, solar pumps, and solar deterrent lights are working to reduce this conflict. However, all solutions have their limitations. Solutions like these will have to be periodically advanced because animals also gradually work around them. Also, to encourage more people to adopt them, the government should make them affordable through subsidies.

This emphasizes that human interference in wildlife areas should be reduced. In our next article, we report on the forest department’s integration of solar energy in forest patrolling and wildlife conservation.

This story was produced with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Tiger. Man. Man-eater Tiger. What or Who Turns Them Man-eater?

After Tragedy, Families Face Delays in Tiger Attack Compensation

Stay connected with Ground Report for underreported environmental stories.

Follow us onX, Instagram, and Facebook; share your thoughts at greport2018@gmail.com; subscribe to our weekly newsletter for deep dives from the margins; join ourWhatsApp community for real-time updates; and catch our video reports on YouTube.

Your support amplifies voices too often overlooked, thank you for being part of the movement.